The ratification of the Constitution in 1788 ushered in a new era in the United States. The times were not without discord—domestic, foreign, and within the government itself—as the nation implemented a new structure that inevitably brought forth many opinions on how best to govern the nation.

Among the most dramatic changes in the new Constitution was the presidency, first held by George Washington. Noted for many accomplishments, Washington is the only president to have swept the Electoral College as he was elevated to the office. Despite his stature and popularity, he was beset by conflict within his Cabinet and in the nation.

In letters to members of his Cabinet (Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, and Attorney General Edmund Randolph) in 1792, Washington described the trials and the dangers that the new nation faced and proposed remedies. The similarity to modern times is striking, but more importantly, we would do well to remind ourselves of his counsel on this 288th anniversary of his birth.

To Randolph, he lamented “the Seeds of discontent, distrust, and irritations which are so plentifully sown, can scarcely fail to produce this effect.” He continued with a comment on the ensuing result of such conduct: “to Mar that prospect of happiness which perhaps never beamed with more effulgence upon any people under the Sun; and this too at a time when all Europe are gazing with admiration at the brightness of our prospects. And for what is all this?”

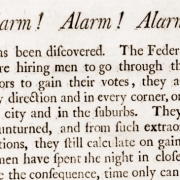

Washington not only attributed to political figures the conditions that filled him with “painful sensations,” he recognized that gazettes and newspapers exacerbated the tensions. He wrote to Randolph, “I shall be happy in the mean time to see a cessation of the abuses of public Officers, and of those attacks upon almost every measure of government with which some of the Gazettes are so strongly impregnated.” He added that “the constant theme for News-paper abuse” is carried out “without condescending to investigate the motives or the facts.” The charge recurs in the letter to Hamilton. “I would fain hope that liberal allowances will be made for the political opinions of one another; and instead of those wounding suspicions, and irritating charges with which some of our Gazettes are so strongly impregnated, & cannot fail if persevered in, of pushing matters to extremity, & thereby tare the Machine asunder . . . ”

The dangers of the internal dissension and the external attacks were real to Washington. Should they not heed his call for “mutual forbearances and temporizing yieldings on all sides,” he wrote to Hamilton, he feared for the governance of the country: “Without these I do not see how the Reins of Government are to be managed, or how the Union of the States can be much longer preserved.”

Washington offered counsel on the posture that he wished all should adopt in response to the “wounding suspicions and irritating charges” as the gazettes risked “pushing matters to extremity.” To Hamilton he expressed his earnest wish “that balsam may be poured into all the wounds which have been given, to prevent them from gangrening.”

Washington also invoked the theme of charity to the recipients of his letters. He lamented on the one hand “that men of abilities, zealous patriots, having the same general objects in view, and the same upright intentions to prosecute them, will not exercise more charity in deciding on the opinions and actions of one another” and on the other hand that their ideas risk being forejudged “without more charity for the opinions & acts of one another in Governmental matters . . . before they have undergone the test of experience.”

The French phrase plus ça change, plus c’est la mȇme chose (“the more things change the more they stay the same”) may well be applicable to Washington’s times and ours, but his counsel points us to a necessary correction for the good of the country:

How unfortunate would it be, if a fabric so goodly, erected under so many Providential circumstances, and in its first stages, having acquired such respectability, should, from diversity of sentiments or internal obstructions to some of the acts of Government . . . should be harrowing our vitals in such a manner as to have brought us to the verge of dissolution. Melancholy thought! But one, at the same time that it shows the consequences of diversified opinions, when pushed with too much tenacity; it exhibits evidence also of the necessity of accommodation; and of the propriety of adopting such healing measures as may restore harmony to the discordant members of the Union, and the Governing powers of it.