Well, at least they’re now being honest about it. A headline this week in The Guardian reads: “Ending climate change requires the end of capitalism. Have we got the stomach for it?”

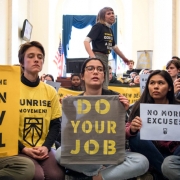

The article, by Phil McDuff, goes on the discuss the “Green New Deal” currently being peddled in the US Congress, and declares a radical turn toward socialism is really at the heart of saving the planet from climate change:

The radical economics isn’t a hidden clause, but a headline feature. Climate change is the result of our current economic and industrial system. GND-style proposals marry sweeping environmental policy changes with broader socialist reforms because the level of disruption required to keep us at a temperature anywhere below “absolutely catastrophic” is fundamentally, on a deep structural level, incompatible with the status quo.

The “status quo,” we have now is a form of capitalism that is highly regulated by states, manipulated by immensely powerful central banks, and distorted by global NGOs like the World Bank. Nevertheless, this system contains enough of a semblance of market-based freedom that many leftwing ideologues regard it as a type of radical laissez-faire capitalism marked by unrestrained and fossil-fuel powered consumption.

Not surprisingly, they think this system must be abolished.

Unfortunately for the billions of human beings who have benefited from what market freedom exists, the new green-socialist global state imagined by McDuff will undo decades of gains against grinding poverty — gains enjoyed by the world’s most at-risk and poorest populations.

The Decline of Poverty — and Its Effects — In the Developing World

Quality of life indicators have been consistently moving upward in recent decades.

Global life expectancy is increasing, especially in the poorest parts of the world. Child mortality is going down. Malnourishment is down. Access to clean water and sanitation is increasing. Literacy is increasing. Extreme poverty is rapidly declining. Access to electricity has grown.

The biggest gains tend to be in Africa and South Asia where the world’s worst poverty has been historically found.

Moreover, we have yet to observe evidence that these trends will be reversed due to climate change.

This doesn’t stop advocates for climate-change socialism like McDuff from predicting disaster. Indeed, in a July 2018 article, McDuff predicts the effects of climate change will be so disastrous that not even oil companies will benefit from their rapacious fossil fuel mongering.

Hazy Disaster Metrics

But what exactly will this global disaster look like? McDuff can point to no details or examples. He can only predict the coming disasters will be measured in “the lives lost, the homes flooded, the farms wasted away to drought.”

Yet, the observed trends suggest this simply isn’t happening. Moreover, McDuff can’t even point to rising deaths from natural disasters, which we are so often told are the chief currency of the coming climate apocalypse.

In reality, deaths from climate-caused natural disasters have gone into steep decline. This is why efforts to predict coming natural-disaster-fueled doom rely on dollar amounts and property damage, which naturally grow over time as homes and machines become more complex and more expensive.

But any growth in human casualties simply can’t be found, and this is largely a byproduct of the wealth surpluses fueled by what moderate amounts of market freedom we have. Thanks to centuries of capital accumulation in market societies, even ordinary people increasingly have access to better medical care, infrastructure, and disaster aid undreamed of in previous generations.

Do What We Say: Or Face Total and Utter Extinction

“So what?” proponents of carbon taxes and climate regulation will say. “Sure, the standard of living may decline, but what’s that compared to total global destruction?”

This sort of hyperbolic language, isn’t an exaggeration on my part. Advocates for climate-change regulations routinely rely on this sort of language precisely because they know the cost of implementing their policies comes at a very high cost. Thus, the choice between their policy and alternatives must be framed as a choice between climate socialism or total extinction.

Indeed, when we examine the proposals in more detail, such as October’s report released by the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), we find that the costs of implementation are immense.

After all, the fundamental premise behind most climate-change-prevention schemes is to regulate energy production, reduce access to cheaper forms of energy, and then replace part of that lost capacity with subsidized new forms of green energy. These subsidies require pulling wealth out of the productive economy and funneling it into special government-favored “green” industries which will receive subsidies — after the state bureaucracy takes its cut, of course. The more expensive products offered by these industries would not have been purchased without the subsidies, and without the coercive regulations designed to reduce choice in energy consumption.

We’re told this sort of extensive state control of one of the economy’s most fundamental resources — i.e., energy — must happen because the only alternative is the total destruction of planet earth.

One does not need to be some sort of hard-core laissez-faire libertarian to see the problem. Even economist William Nordhaus, who has been hailed as a champion of climate-change policies, found that recent carbon-tax and regulatory schemes were so costly, that it would be better to do nothing.

It’s also important to remember these costs are not mere aggregate numbers on a spreadsheet somewhere.

Declaring War on Rising Standards of Living

The effects of these climate-control schemes would come down hardest on people in the poorer parts of the world. Energy consumption is high in the rich world, but the demand for growing access to electricity, personal transportation, and heating-and-cooling technologies are highest in the developing world.

Access to these technologies will be increasingly important as climate change occurs. People the world over will need heating and air conditioning. They’ll need water filtration technology. They’ll need better insulated homes. They’ll need appliances that improve sanitation and free human beings to engage in higher-productivity labor.

But the new green socialism is an immense obstacle to all of this.

Moreover, people in the developing world are still in the process of gaining access to labor-saving and life-changing machines like washing machines. Electric devices such as these improve daily life — an improvement felt especially by women — in ways modern westerners forgot about long ago. Yet, manufacturing and powering machines such as these is costly, and the more affordable energy is available, the more people will gain access.

First-World Chauvinism

This is why statistician Hans Rosling saw a fundamental conflict between well-meaning first-world activists and ordinary people in the developing world.

When speaking to environmentally-conscious audiences, Rosling noted many in the audience insisted that “No, everybody in the world cannot have cars and washing machines.” For these activists, the imperative of lowering energy usage simply demands it.

But, pointing to a photo of a low-income women slaving over a wash basin, Rosling asks: “How can we tell this woman that she isn’t going to have a washing machine?”

It’s a good question, and it’s also a reminder that much of the talk over carbon taxes and climate regulations smack of first-world chauvinism. The rich world already has its cars and its washing machines. Sure, a global climate scheme would reduce the wealth of people in the rich world, but the impact in China, India, Africa, and South America — where most live closer to subsistence levels —would be far more devastating.

For many environmentally-minded suburban upper-middle class people in North America and Europe, this is just tough luck and bad timing for everyone else.

Ryan McMaken (@ryanmcmaken) is a senior editor at the Mises Institute.