You’d think a new species discovering its niche would be fragile and susceptible to extinction – let’s say a 10% chance of extinction in a given period – while an old species had proven its might, and has, say, a 0.01% chance of extinction.

But when Van Valen plotted extinctions by a species’ age, it looked more like a straight line.

Some species survived a long time. But among groups of species, the probability of extinction was roughly the same whether it was 10,000 years old or 10 million years old.

In a 1973 paper titled A New Evolutionary Law, Van Valen argued that “the probability of extinction of a taxon is effectively independent of its age.”

He said that’s the case for two reasons.

One, competition isn’t like a football game that ends with a winner who can then take a break. It never stops. A species that gains an advantage over a competitor instantly incentivizes the competitor to improve. It’s an arms race.

Two, some advantages create new disadvantages. Most species tend to get bigger over time because big things are strong. But being big also makes you slow, clumsy, and unable to hide. “The tendency for evolution to create larger species is counterbalanced by the tendency of extinction to kill off larger species,” one study wrote.

Evolution is the study of advantages. Van Valen’s idea is simply that there are no permanent advantages. David Jablonski of University of Chicago described it: “Everyone is madly scrambling, getting better all the time, but no one is gaining ground. A species can’t get far enough ahead of the pack such that it would be extinction-proof.”

No one’s ever safe. No one can ever rest.

Van Valen called it the Red Queen model of evolution. In Alice in Wonderland, the Red Queen is a scene where Alice finds herself in a land where you have to run just to stay in place:

However fast they went, they never seemed to pass anything. ‘I wonder if all the things move along with us?’ thought poor puzzled Alice. And the Queen seemed to guess her thoughts, for she cried, ‘Faster! Don’t try to talk! Keep running!’

“Keep running” just to stay in place is how evolution works.

It’s how business and investing work, too.

There are 32 million businesses in the United States. The Bureau of Labor Statistics tracks how many of them die each year, and how old they were at death.

Dig through the numbers and one thing’s clear: there is no age at which business gets easy.

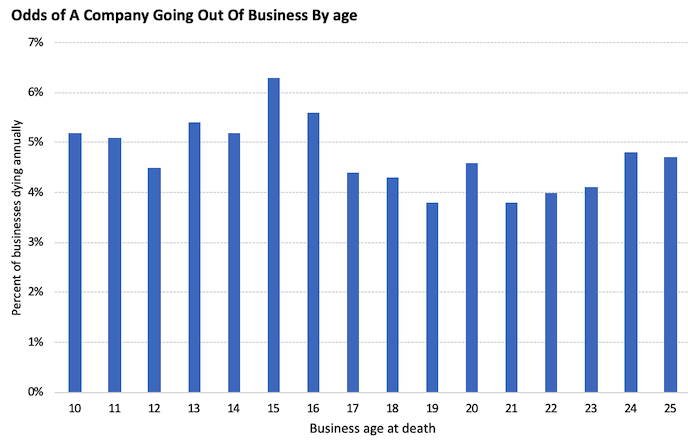

Companies have a high failure rate in their first three to five years. Then the challenges plateau. Averaged across industries, a business in its 25th year has roughly the same probability of dying as it did in its 10th year:

Source: BLS

What’s interesting about this is that the average business cycle – the time between recessions – is about eight years. So a 24-year-old business has likely endured three recessions. It’s been battle-tested. It’s learned from ups and downs. But it’s still as likely to die over the coming year as it was 15 years ago.

Same thing for public companies.

Companies tend to go public when they’re mature and have things figured out. But having things figured out is fleeting. J.P. Morgan Asset Management published the distribution of returns for the Russell 3000 from 1980 to 2014. Forty percent of all Russell 3000 components lost at least 70% of their value and never recovered.

If you invest in 100 high-risk startups, you probably expect 40 of them to fail. Then if you move on to investing in 100 mature public companies, 40 of them will probably fail, too. They might stick around longer than the startups, but the end result is the same.

What does that say about competitive advantage?

Or the concept of moats?

It says that those things, to the extent they exist, are rarely permanent.

Just like Van Valen’s view of nature, things evolve but never actually become better adapted, because threats are always changing. Black Rhinos survived for 8 million years before being killed off by poachers. Lehman Brothers adapted and prospered for 150 years and 33 recessions before it met its match in mortgage-backed securities. Poof, gone.

Startups have their obvious challenges. They’re trying to find their niche. But once that niche is found and perfected, old companies discover a whole new minefield. They get complacent, bureaucratic, cocky, and unwilling to discard what once worked so well. There is never a point where a company can indefinitely coast along, cashing the chips of past success. Everyone has to keep running.

Same for investing strategies.

It’s easy to think investing is like physics, with set laws that never change. But it’s not. It’s like Van Valen’s evolution, where “success” is just a brief respite before the next competitor shows up and old skill becomes meaningless.

In his book Investing, Robert Hagstrom wrote about strategies that once worked but eventually withered:

In the 1930s and 1940s, the discount-to-hard-book-value strategy was dominant. After World War II and into the 1950s, the second major strategy that dominated finance was the dividend model. By the 1960s investors exchanged stocks paying high dividends for companies expected to grow earnings. By the 1980s a fourth strategy took over. Investors began to favor cash-flow models over earnings models. Today it appears that a fifth strategy is emerging: cash return on invested capital.

I’d update this. Since about 2010 the strategy that works is just revenue growth.

“If you are still picking stocks using a discount-to-hard-book-value model or relying on dividend models to tell you when the stock market is over or under-valued, it is unlikely you have enjoyed even average investment returns,” Hagstrom writes. You’ve likely gone extinct.

There is never a time when an investor can discover an investing strategy and be confident it will continue working indefinitely. The world changes, and competitors create their own little twist that exploits and snuffs out your niche.

Same with careers.

And job skills.

And relationships.

And countries.

It’s hard to accept that you have to put in a ton of work just to stay in place, but that’s how it works. Keep running.