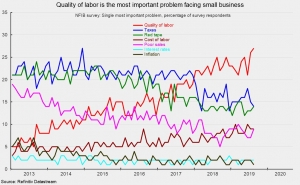

The latest survey of small business contains a surprise. Or maybe it is not a surprise if you are or know a small business owner. Over the last six years, the concerns of taxes and regulations are being eclipsed by a new number-one concern: the lack of quality in the workforce.

Now, what does quality in staffing mean? It could mean skills. In the U.S., we generally pin people to chairs for seventeen years and then throw them into the workforce with a message: go be valuable. But they often haven’t really learned things that are valuable in the workplace. Certainly their political views and cultural sensitivities count for nothing in terms of the bottom line.

Quality could also mean attitude. Are they hard working, creative, resourceful, and generally thrilled about the prospect of doing a good job? Some people have all these traits naturally, so it’s not a problem. But for many others, these traits have to be learned, and they’ve had no opportunity to learn.

It could also mean basic discipline, such as showing up on time, not spending your day on your smartphone, doing the tasks assigned to you, not being an entitled jerk by caring nothing for the community of productivity of which you are supposed to be part.

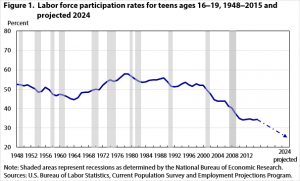

Most likely, it is a combination of all these things. My own pet theory is suggested by the above commentary: to know how to work, it really helps to have worked. Right now, labor force participation by teens is at historic lows, having fallen from two-thirds 30 years ago to less than 30% today.

Yes, this all really began to tumble after the Great Recession. The teen job market briefly collapsed and their teachers and parents never really leaned against the trend. Now it is commonly said that holding a job is nothing but a distraction from the all-important job of getting a degree. Parents are convinced that this is the path to a good life, forgetting that a degree can be useful for getting in the door but it doesn’t do the work for anyone. People still have to show up on time, complete tasks, and generally care about building a career. This is what is missing.

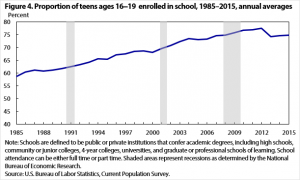

Just look at the number of people from 16-19 who are enrolled in school. It’s between 70% and 75%. It’s the inverse of those working. Not a coincidence.

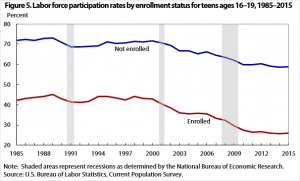

Admittedly, however, labor force participation is falling equally for both the enrolled and unenrolled.

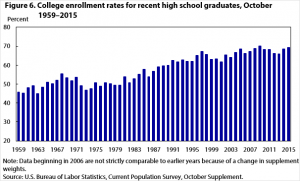

Meanwhile, college enrollment is booming (50% to almost 70% in 30 years) but evidently it’s not helping to convince employers that these kids can get the job done. Indeed, the mass handing out of college degrees could have a perverse effect on work ethic: I’ve got my paper so you have to pay me just for being my awesome self!

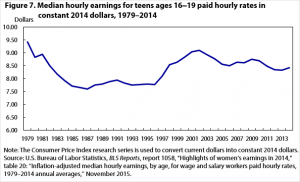

Now you might say that young people aren’t working because the wages are too low, and perhaps this is due to the low minimum wage. This is not true. Wages in real terms are the same now as they were in 1983, during which time labor force participation was vastly higher.

It’s very possible that we are seeing the perfect storm here. The Great Recession hit about the same time as smartphones were invented to provide young people the ultimate distraction from reality. They have mastered the art of posting on Instagram with the aspiration of becoming an influencer but never learned how to stick to a task and provide value to an actual firm.

Another potential problem here is the vogue for “owning your own business” and “being an entrepreneur.” That might sound lovely in some ways, but the reality is that in order to start a successful business, you have to know the ins and outs of an industry. If you don’t, you won’t succeed. In the meantime, this aspiration might just create a kind of mental intransigence against having a boss, doing assigned tasks, and taking home a paycheck.

What’s more, there is no evidence that the goal of starting new businesses is working out for these people either. “Business applications that have relatively high likelihood of turning into job creators,” says the US Census, “have not fully recovered after the Great Recession, and their quarterly volume is still far below its pre-recession levels.”

Finally, consider just how vexing are taxes and regulations. These are job killers and business killers. For anything to ascend higher than those concerns, you know it has to be serious. I’m concluding from all of this that America has a skills problem and a work-ethic problem, perhaps an overly-entitled problem.

The remarkable feature of this issue is that it comes down to something anyone can change, their own personal values and life priorities. Moreover, this creates a real opportunity for those who decide to be valuable by being a good worker with skills. It means that you can very quickly become gold in the marketplace for labor. (That’s especially true with the diminished opportunity for using immigrant labor.) The depressing data actually amounts to a fantastic opportunity for those who choose to take advantage of it.

Jeffrey A. Tucker is Editorial Director for the American Institute for Economic Research.