As the 20th century drew to a close, democracy was on the march. The Soviet Union was gone, Nazism was a distant nightmare and every continent showed signs of moving toward free elections and the rule of law. All of humanity was finally coming to recognize the transcendent principles of democratic liberty and equality—or so many observers concluded.

Looking back, the reasons for democracy’s appeal in those heady days appear more complicated. A big part of it had to do not with noble ideals but with economic success. The world’s richest countries were democracies, and the rest of the world wanted to be rich too. Today, global wealth is shifting to more authoritarian parts of the world—and it isn’t clear how well democracy, without every material advantage on its side, will fare in the competition.

Since the 1890s, countries like the U.S., Great Britain and a small band of other democracies have dominated the global economy. As recently as 1995, 96% of all people who lived in a country with a per capita income over $20,000 (in today’s terms) were citizens of a liberal democracy. With the exception of a few oligarchs perched atop stagnant and repressive societies, only democrats got to enjoy real affluence.

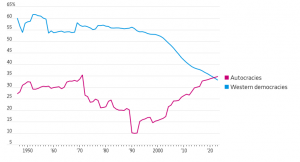

Today’s reality is very different. Our analysis of International Monetary Fund projections shows that sometime in the next five years, the total GDP of countries rated “not free” by Freedom House will surpass that of Western democracies. The combined economies of democratic countries like the U.S., Germany, France and Japan will be smaller than those of autocracies like China, Russia, Turkey and Saudi Arabia.

If the West is to navigate this new world successfully, it will need to understand how the scales tipped so rapidly from democratic dominance to authoritarian resurgence. One part of the explanation is democratic reversals in large economies, thanks to the efforts of strongmen such as Russia’s Vladimir Putin and Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan. If democracies like Brazil, India and South Africa experience similar erosion in the years ahead, the relative power of autocratic rulers will keep growing.

The Growing Economic Power Of Autocracies

But an even more important factor has been the rise of authoritarian capitalism. Before the 21st century, autocratic regimes that reached a relatively high level of per capita income tended either to stop growing, like the Soviet Union, or to become democratic, like military regimes in Asia, Latin America and southern Europe. Countries such as Singapore, which kept growing without becoming a true democracy, were explained away as small exceptions that proved the rule.

This limitation still applies to autocratic regimes like North Korea and Venezuela, which have clung to strict state control of the economy. But a growing number of countries have learned to combine autocratic rule with market-friendly institutions, and they have continued growing economically well beyond the point at which democratic transitions used to occur.

Today, 376 million people live in deeply unfree countries—including Russia, Kazakhstan and the Gulf states—that have per capita incomes above $20,000 in terms of purchasing-power parity. In China’s coastal region, average incomes have already risen above this level, and the major cities have surpassed $35,000. When China as a whole crosses above $20,000 in per capita income, which the IMF estimates will happen next year, 1.8 billion people around the world will live in upper-income authoritarian regimes.

This development carries enormous implications for the future of democracy. The last time the democratic world faced a serious challenge to its economic and technological primacy was after the Soviet Union’s launch of Sputnik, the world’s first artificial satellite, in 1957. Buoyed by postwar reconstruction and the addition of seven new vassal states in Eastern Europe, the Soviet bloc had seen its GDP increase from one-fifth of the U.S. level in 1945 to over half that level by 1958. A few years later, Paul Samuelson, the Nobel Prize-winning economist, predicted in his widely used introductory textbook that the GDP of the Soviet Union would surpass that of the U.S. by 1984.

Hopes for the U.S. to grow its way out of the current predicament are no more than fantasies.

It never happened, of course. By 1969, an American flag was fluttering on the moon and economic growth in the U.S. once again outpaced that of the Soviet bloc. Living standards under communism never reached those of the West. Subsequent editions of Samuelson’s textbook kept pushing the point at which he projected the Soviet economy would overtake that of the U.S. into the ever more distant future.

Today, however, there is less reason for confidence in the eventual economic triumph of democracy. In 1957, the U.S. and its democratic allies in Europe and Japan accounted for almost two-thirds of the global economy—three times more than the Eastern bloc plus China. Sputnik may have made Americans nervous, but the West was still economically dominant. The real question was whether it had the political resolve to translate its material power into geopolitical hegemony.

In 2019, by contrast, no amount of political resolve will reverse the fact that Western democracies account for little more than a third of the world economy. Given the radical shift in world-wide population and productivity that we have witnessed in the recent decades, it would be naive to expect North America and Western Europe to reign supreme again anytime soon. Hopes for the U.S. to grow its way out of the current predicament are no more than fantasies.

Whether democracy or autocracy rules the world in the 21st century is thus likely to depend on a number of pivotal countries that could end up as part of either camp. If countries such as India, Nigeria and Indonesia manage to build stable and affluent democracies, the principles of liberty and equality have a chance to maintain and extend their influence in the coming decades. But if these crucial “swing states” turn autocratic while becoming rich, democrats will have a harder time making their case.

As the history of the 20th century shows, freedom tastes much sweeter when it seems to be the gateway to prosperity.

Mr. Foa is a lecturer in political science at the University of Melbourne. Mr. Mounk is an associate professor of political science at Johns Hopkins and the author of “The People Versus Democracy: Why Our Freedom Is in Danger and How to Save It.”

PHOTO: GILLES SABRIE/BLOOMBERG NEWS