In recent congressional testimony Dr. Anthony Fauci, the primary architect of the Trump administration’s COVID response, painted a bleak picture about the United States’s ability to contain the pandemic. According to Fauci’s narrative, the United States is experiencing a resurgence in regional COVID outbreaks because it failed to sufficiently lock down back in March, and failed to comply with the existing lockdown orders. Fauci specifically contrasted this situation to several European states that imposed lockdowns around the same time, claiming the latter as a successful model for COVID containment.

There are several immediate problems with Fauci’s arguments, including the fact that COVID cases are showing clear signs of a summer resurgence in the same European countries that allegedly tamed the virus through harsh lockdowns in the spring. The American news media however has seized on Fauci’s narrative, and used it to call for renewed lockdowns. The New York Times and the Washington Post both editorialized in favor of a second stricter wave of nationwide lockdowns lasting until October – this despite there being no clear evidence that lockdowns actually work at taming the virus.

So how does the evidence behind this narrative stand up under empirical scrutiny? Let’s consider the claims.

Did the United States react too late?

According to the pro-lockdown narrative, the United States is experiencing a second COVID wave because it took a lackadaisical approach to locking down. We allegedly closed too late and reopened too early, leading to a failure to tame the virus in the spring. This same narrative often holds up Europe as a counterpoint for what a cautious, responsible, and evidence-based reopening process supposedly looks like.

I’ve investigated this claim previously using start and end dates for the lockdowns in various countries. Simply put, it is entirely without merit.

Most of the United States went into lockdown during the second and third weeks of March, following a set of Trump Administration recommendations that were based on the now-discredited Imperial College epidemiology model of Neil Ferguson. In total, 43 of 50 American states imposed shelter-in-place style lockdowns, with the holdouts consisting almost entirely of rural western states with low population density and few signs of the outbreaks that plagued the cities of the northeast at that time.

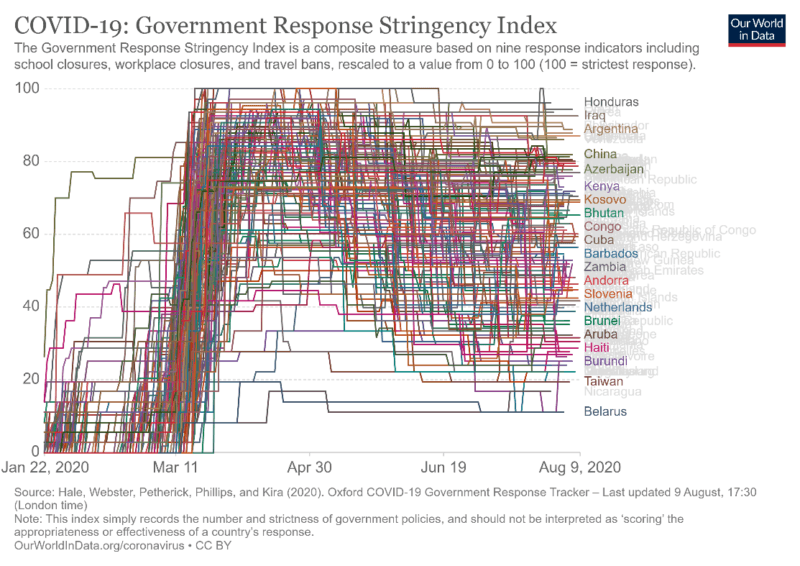

As far as timing goes, the US lockdowns came into effect at almost exactly the same time as not only Europe but the majority of the world. A few early outbreak hotspots such as Italy preceded this shutdown by about 2 weeks, and a handful of countries (Sweden, Taiwan, Belarus) bucked the international trend. But otherwise, the timeline clearly confirms that the American response directly coincided with most other countries.

Did the US reopen too early?

What about reopening then? As I also previously discussed, the United States has generally lagged behind most of Europe in removing the lockdown measures from March and April. Most European countries began their reopening efforts in late April or early May. As of June 1st, the United States’s COVID response stringency score – a measurement of lockdowns and related closures maintained by Oxford University’s Blavatnik School of Government – outranked every Western European nation except for Ireland and Belgium.

Although some US states such as Georgia, Colorado, and Texas began to reopen in late April, this process began no earlier than the first of their European counterparts. Far more often, American states have lagged behind Europe by as much as a month or longer. Several hard-hit states such as New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts, as well as population centers such as California, adopted a strategy of extremely cautious and tepid reopening. Many extended their shelter-in-place mandates until late May or even June. They also adopted lengthy bureaucratic reopening guidelines that spread the process over several phases to the point that most of the US remains more heavily restricted than Europe to this very moment.

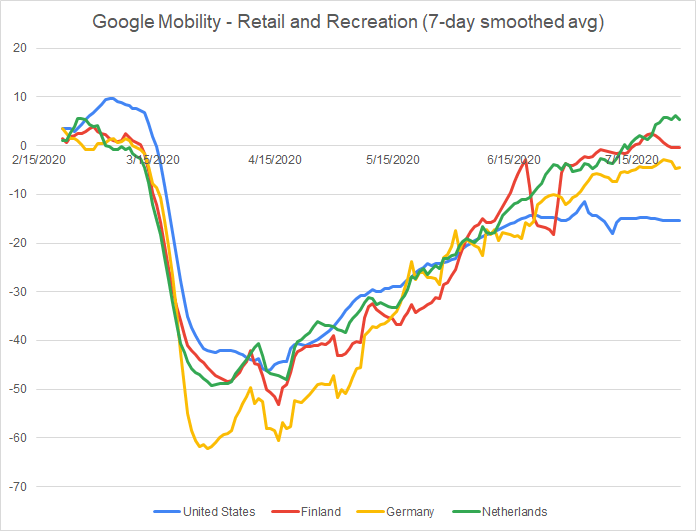

Equally revealing, we may still see the clear effects of the United States’ slower reopening in key metrics from Google’s publicly released cell phone mobility data. From the start of the lockdowns in March until roughly mid-May, US mobility patterns map almost identically onto at least three European countries that similarly locked down: Germany, the Netherlands, and Finland. All three of these countries began to reopen during the first and second weeks of May. Large swaths of the US, and particularly its population centers, remained under lockdown or only a heavily restricted reopening at this point.

The divergence in policies is clearly visible in Google mobility patterns. Whereas Germany, Finland, and the Netherlands all returned to near-normal levels of mobility in late May and June, the United States’ reopening process stalled around the same time and remains at a plateau that is still well-below normal.

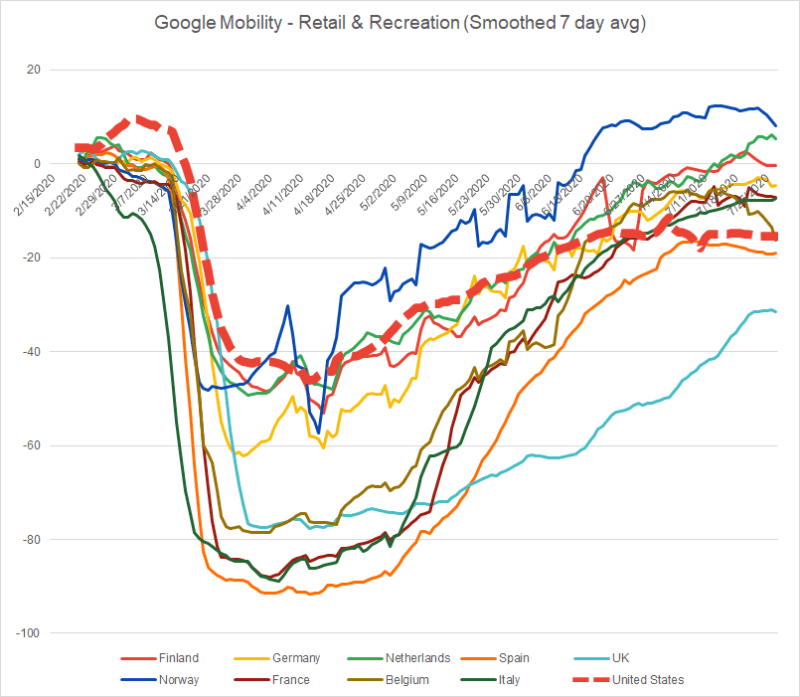

The pattern also appears when we compare the US to other European countries, including those that – at least temporarily – had more stringent shelter-in-place orders in effect. In most European states, mobility patterns rebounded past the United States in early to mid-June after the American reopening stalled. Today, only the UK exhibits a more pronounced closure than the US while Spain similarly plateaued.

The pattern also appears when we compare the US to other European countries, including those that – at least temporarily – had more stringent shelter-in-place orders in effect. In most European states, mobility patterns rebounded past the United States in early to mid-June after the American reopening stalled. Today, only the UK exhibits a more pronounced closure than the US while Spain similarly plateaued.

Were the US lockdowns less stringent than Europe?

According to Fauci’s testimony, the US imposed far less-stringent lockdown measures than Europe, which he then attributes to the resurgence in cases. This is a complex question to answer because European states varied quite a bit in their lockdown policies and the duration of each. That much noted, nation-level scores such as the Oxford stringency index belie the claim.

The Oxford index uses a 0 to 100 score to measure stringency, awarding points for a variety of policies including border closures, school closures, event cancellation, non-essential business closures, and shelter-in-place mandates, as well as other non-pharmaceutical interventions such as public information campaigns. From the start of the lockdowns in mid-March until June, the United States stringency score sat at 72.69 out of 100. This was comparable to the peak score for the Netherlands (79.63), Germany (73.15), Norway (79.63), Denmark (72.22), and Switzerland (73.15). It was also above Finland’s peak score (60.19) as well as Sweden (40.74), the latter of which did not go into lockdown and only adopted more modest social distancing guidelines.

The US did have a less-stringent score than some of the hardest-hit European countries – but only temporarily. Italy (93.52), France (90.74), Ireland (90.74), and Spain (85.19) imposed more stringent lockdowns than the US, but only for about two months between March and April before rapidly relaxing their restrictions.

Fauci presumably had this much smaller list of countries in mind when he claimed they employed a stricter lockdown than the US, although the evidence is flimsy at best. Measured on a per-capita fatality basis, Italy and Spain had more severe outbreaks than the US, and France currently sits at near-parity. These patterns may change, particularly as each country experiences a second wave in the late summer, but they do not exhibit even modest inverse correlation with the lockdown policies of each country. If anything, the more-stringent policies in locales such as Italy and Spain were likely reactive – they were imposed out of desperation in response to a viral outbreak that appeared to be spinning out of control in these early months. Indeed, the mobility data suggest as much with the most severe declines from the March-April period occurring in the hardest-hit locales and generally starting slightly before they went into lockdown.

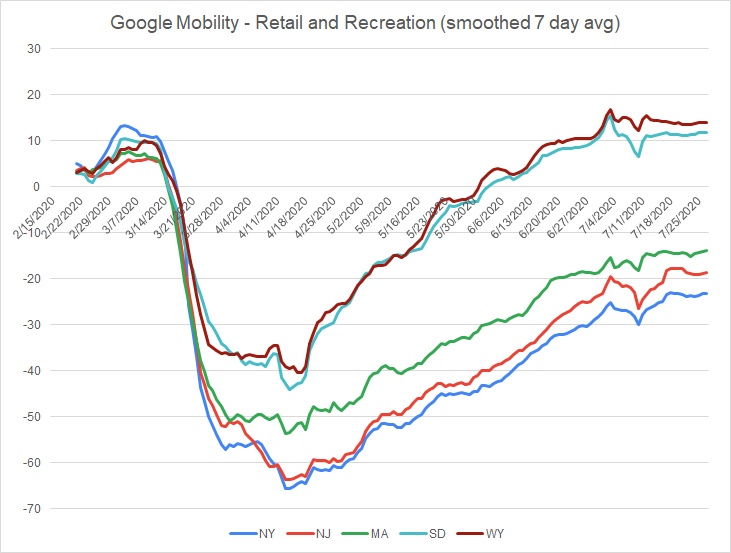

Returning to the United States, we see similar variation in the mobility declines when we compare hard-hit states such as New Jersey, New York, and Massachusetts with non-lockdown states such as Wyoming and South Dakota.

These data suggest the claimed effects of more-severe lockdowns cannot be separated from either severity of the outbreak in a given region or the voluntary behavioral responses to the same. This problem afflicts both the worst-hit European countries and the worst-hit US states, but it does not illustrate a failure to impose sufficient lockdowns in each.In sum, there’s no clear evidence that aligns with Fauci’s claims about European lockdown stringency. On the whole, the US locked down at a comparable level to several European countries according to the Oxford index, with the exception of the hardest-hit locales – and those locales only surpassed us during their peak outbreaks of March and April, followed by a much more rapid relaxation of the restrictions. Meanwhile the US has clearly retained its lockdown policies for longer than almost all of Europe, and continues to stall behind Europe’s reopening process.

These data suggest the claimed effects of more-severe lockdowns cannot be separated from either severity of the outbreak in a given region or the voluntary behavioral responses to the same. This problem afflicts both the worst-hit European countries and the worst-hit US states, but it does not illustrate a failure to impose sufficient lockdowns in each.In sum, there’s no clear evidence that aligns with Fauci’s claims about European lockdown stringency. On the whole, the US locked down at a comparable level to several European countries according to the Oxford index, with the exception of the hardest-hit locales – and those locales only surpassed us during their peak outbreaks of March and April, followed by a much more rapid relaxation of the restrictions. Meanwhile the US has clearly retained its lockdown policies for longer than almost all of Europe, and continues to stall behind Europe’s reopening process.

Is the US less compliant with public health mandates than Europe?

Although it is more of an implication than a claim from Fauci’s testimony, the media has embraced a final narrative that asserts the United States is less-compliant than Europe in obeying public health mandates. If this were true, the US might have nearly identical policies in place on paper and yet still perform poorly compared to European states where compliance was higher.

Unfortunately, compliance with public health mandates during COVID is difficult to measure. One exception is also a flashpoint of political debate in its own right – the wearing of masks.

Fortunately, extensive survey data exist to track mask-wearing habits of the public since the start of the pandemic. Last month the Economist magazine published a comparison of available survey response rates over time. Briefly summarized, roughly 70% of the US population indicates that it currently wears masks in public places. Mask-wearing has exceeded 60% in the US since early April, despite following several weeks of contradictory advice on masks from public health officials including Fauci himself. US mask-wearing rates are also higher than Canada. It also lags only slightly behind the roughly 80-90% usage rates in east Asian countries, where masks were already a much more common pandemic response.

The fascinating twist to the mask story though is Europe. Mask usage soared in Spain, Italy, and France during the peak of their outbreaks, topping just over 80% or slightly above the US. But mask-usage in Northern Europe remains far below US levels even to this day. No Scandinavian country topped 20% in mask usage even at the April peak of the pandemic (they’ve since declined in number), and the United Kingdom hovers at only 30% in the most recent polling from late June. All said, US mask-wearing is only slightly behind the worst-hit parts of Southern Europe and well ahead of Northern Europe. Insofar as masks may be used to signal compliance with a specific and high-profile public health mandate, there does not appear to be any evidence that the US has fallen behind other countries.

Making sense of it all

Collectively, the data above offer no clear support behind four major claims of the pro-lockdown narrative being spun by American media outlets in the wake of Fauci’s testimony. To the contrary, several data points directly conflict with both the express claims of Fauci’s testimony and its implied interpretations, as advanced by outlets such as the New York Times. The US response to the COVID-19 pandemic largely paralleled Europe in its early months, and only diverged from that pattern in the opposite direction of the media’s narrative. While Europe began to reopen and did so earlier and faster, the United States reopening has stalled.

What then are we to make of the recent case surges in the southern US and on the west coast? Most likely, they reflect the regional nature of the virus’s spread as it migrates into population centers than largely escaped the first wave in March and April. The threat of further spread remains a public health concern, particularly as it pertains to vulnerable populations such as nursing homes. But its pattern has little if anything to do with the lockdown orders – an ineffectual approach to mitigating the virus, but also one with severe social and economic harms.

Unfortunately, the pro-lockdown position favored by Fauci and several US media outlets has become a matter of ideological commitment. Whether they are doing so to rationalize the costs we have already incurred from this disastrous approach or to further politicize the pandemic response for a variety of electoral and partisan purposes, they have embraced a pro-lockdown stance that is unchained from any evidence or clear data. It should not be surprising that their accompanying narrative to justify that stance is similarly detached from reality.