This series began with Great Athletes, human achievement in general, and how it is rewarded or punished by society. Our later post titled Mediocrity Worship tacked the other way. If envy is leveraged to punish what is good, what happens when mediocrity is rewarded? The answer boils down to objective versus subjective values, and their consequences.

Henry Rearden and Simone Biles achieved their ambitions by pursuing objective values, through independence. They expanded their consciousness, and invented new standards for a steel alloy and a gymnastics routine, respectively. Their goals and self-respect were unique to them, and deserved an objective system for scoring and rewarding success. By choosing conformity, Peter Keating and Bernie Madoff opted for the approval of others; their self-respect was derived from the subjective whims of their masters. Favorable press and beating the market were their respective rewards, until they turned to dust.

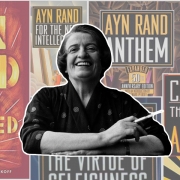

The difference between the former pair and the latter is integrity. In Ayn Rand‘s philosophy, integrity is much deeper than the honesty of fair dealing or the trust of keeping promises. It is the integration of one’s mind and body, the unity of actions and convictions, of rational and steadfast principles for living. In her breakthrough novel The Fountainhead, Rand created such a character in Howard Roark. In 21st century Western art, the classical composer, pianist, and violinist Alma Deutscher is a wonderful example.

Twentieth Century Malaise

According to a March 2020 Wall Street Journal editorial, “Something terrible happened to classical music during the 20th century. The great preponderance of classical music written over the past 75 years is deliberately opaque and aggressively ugly.”

This observation about classical music also applies to 20th century political and educational institutions, and is rooted in the dominant philosophy of the 19th century. The rise of the Bolsheviks in Russia, the Nazis in Germany, and the Communists in China ultimately meant the starvation and murder of nearly 200 million people. This can be directly attributed to the ideas of Immanuel Kant, Friedrich Hegel, and Karl Marx. As Rand explains in her novel Atlas Shrugged, their mindset demands that “Nobody is right or wrong, we’re all in this together.”

Alma Deutscher faces the same relentless pressure to conform to their subjective values, and refuses to offer herself as a human sacrifice,

Lots of people have been telling me that I have to compose music that will reflect the ugliness of the modern world. I don’t want to do this. I want to compose music that I find beautiful.

The Wall Street Journal continues, “Some recent composers have resisted the tendency to equate serious with dissonant or difficult – Arvo Pärt in Estonia, the late Dominick Argento in America. But none have done so in quite the guileless manner of English composer Alma Deutscher.” For example, in an interview with CBS Alma says,

I love getting the melodies. It’s not at all difficult to me. I get them all the time. But then actually sitting down and developing the melodies and that’s the really difficult part, having to tell a real story with music.

Composing beautiful music that tells a real story harkens the listener back to the 19th century, the Age of Reason, and ethically superior era of great Romantic art. Its artwork integrated the other branches of philosophy and reflected society’s guiding principles. Yet its morality of self-creation and capitalism came to a crashing halt with World War I. Great art is difficult to produce in a values-deprived culture, and classical music became “atonal, obsessed with shock value, and incoherent.”

Free Will or Fate

Art tends to express a culture’s philosophy, and it can be the volition of free will or the determinism of fate. Great art can inspire emotions and cognitive development, and illustrate moral principles that guide decisions and actions. As Alma tells us, abstract concepts are complex,

The difficult bit is to sit down with that idea, and to combine it with other ideas in a coherent way. Its easy to throw a soup of ideas that don’t make any sense together. To tweak it and polish it, that takes ages.

Like Howard Roark has clients in order to build, Alma Deutscher has an audience in order to perform her original solos, sonatas, and concertos. It is her fidelity to the integrity of beautiful, inspiring, classical music that make her a singularity. As Roark instructed the Dean of the architecture college that expelled him,

The purpose, the site, the material determine the shape. Nothing can be beautiful unless it’s made by one central idea, and the idea sets every detail. A building is alive, like a man. Its integrity is to follow its own truth, its one single theme, and to serve its own single purpose.

Regarding conformity, Deutscher refuses to acknowledge the subjective morality of our postmodern world. “While her critics don’t fault her for a lack of technical sophistication, they dislike her music for the same reason audiences love it. They object to its traditional tonality, its straightforward emotional appeal, its refusal to acknowledge the repugnance of human life.” This has no effect on her,

People loved it. The audience stood many times. They were elated, uplifted. What matters is what the audience thinks. What the critics write, I don’t read it anyway, doesn’t bother me. I see the reaction of the people. They say what they mean.

Or when asked by his tormentor, “What do you think of me?” Howard Roark replied, “But I don’t think of you.” What Deutscher and Roark have done is expose the smallness of their detractors. By refusing to accept the arbitrary premise that human life is repugnant, they refuse to accept as guilt, their own existence. They refuse to accept that their freedom to create masterpieces is predicated on subservience to the public good. Their integrity is non-negotiable.

Cinderella Story

In an interview with CBS News, Alma relates about one her musical heroes, “Of course, I love Mozart and I would have loved him to be my teacher. But I think I would prefer to be the first Alma than to be the second Mozart.” When asked, “So you improved the cadenza of Mozart? Well, yes” she answered. About her opera Cinderella she says,

I think that it makes much more sense if he falls in love with her because she composed this amazing melody to his poem, because he thinks that she’s his soul mate, because he understands her.

With her, Howard Roark laughs.