It’s an important act of individualism to challenge the conventional narratives the establishment feeds us in order to convince us that their policies are right and their preferences should prevail. Income inequality is a cudgel they use to beat us. No matter how hard we work, no matter how dedicated and ingenious we are in devising new and better ways to serve others in economic exchange, we must give up the value we create to government so that they can redistribute it. Why? Because we are morally bankrupt. What’s the evidence? We have failed to achieve equality, which is the ultimate moral purpose of economic activity. But what if the evidence is wrong, or worse still, mis-reported?

We aren’t stagnating, after all.

Unless you’ve been hibernating in the Himalayas, you must know of the recent surge in economic inequality. It’s not just that the rich are getting richer. The rest of us — say politicians, pundits and scholars — are stagnating. The top 1% have grabbed most income gains, while average Americans are stuck in the mud.

Well, it’s not so. That’s the message — perhaps unintended — from the Congressional Budget Office, which reports periodically on the distribution and growth of the nation’s income. It recently found that most Americans had experienced clear-cut income gains since the early 1980s.

CBO Findings On Income Inequality

This conclusion is exceptionally important, because the CBO study is arguably the most comprehensive tabulation of Americans’ incomes.

Most studies of incomes have glaring omissions. Some only examine before-tax income; others, after-tax. Many don’t include some government benefits — for example, food stamps, Medicare or Medicaid (health programs for the elderly and poor). Others exclude employer-paid health insurance, which is a big item. The CBO study covers all these areas.

It confirms that the rich have catapulted ahead of most Americans, including many with six-figure incomes. The richest 1% of U.S. households had average pretax incomes of $1.855 million in 2015. The growth has been astonishing. From 1979 to 2015, pre-tax incomes of the top 1% jumped 233%. That’s more than a tripling. (All figures are corrected for inflation.)

But it’s not true that no one else had gains. If the bottom 99% experienced stagnation, their 2015 incomes would be close to those of 1979, the study’s first year. This is what most people apparently believe.

Is Income Inequality Growing?

The study found otherwise. The poorest fifth of Americans (a fifth is known as a “quintile”) enjoyed a roughly 80% post-tax income increase since 1979. The richest quintile — those just below the top 1% — had a similar gain of nearly 80%. The middle three quintiles achieved less, about a 50% rise in post-tax incomes.

These seem small, but over four decades, they’re meaningful. It’s doubtful that most Americans would prefer to revert to the world as it was in 1979 — a world without smartphones, the Internet, most cable television or laparoscopic surgery.

Why then the belief in stagnation?

One plausible theory is that the gains in any one year are so small that most people don’t recognize them. Instead, they feel they’re marching in place. The demands on their income — for housing, food, college tuition, vacations and much else — swamp tiny gains.

Economic Stagnation?

Certainly, what’s occurring today is less impressive than the great gains of the 1950s and 1960s, when there was a floodtide of new technologies and products: television, modern appliances (washers, driers), jet travel, air-conditioners and antibiotics, to name a few.Some economists legitimize the stagnation thesis by selective studies and their use of language. For example, former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers has used the term “secular stagnation” — which was coined in the late 1930s — to describe today’s economy.

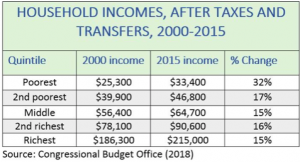

Glance at the table below. It shows that modest income gains were widespread.

For the period 2000 to 2015, it gives the average gain in after-tax and after-transfers (government benefits) income for each quintile, from poorest to richest. The year 2000 was chosen as the base to dispel any notion that income gains occurred in the 1980s or ’90s. Interestingly, the relative gain for the poorest quintile was about twice the increase of other quintiles (again: a quintile represents a fifth of the population).

Reality of Income Inequality

Although higher incomes could — in theory — reflect generous tax cuts, that doesn’t appear to be the case. In 2015, the richest 1% paid an average federal tax rate of 33%, close to the 1979 rate of 35%.

With income inequality rising, it’s not surprising that richer groups have actually provided an increasing share of federal tax revenues. In 2015, the richest quintile of Americans paid 69.5% of revenues, up from 55.1% in 1979. The share of the top 1% (included in the richest quintile) went from 14.1% in 1979 to 26.2% in 2015.

(Note: Because President Trump’s tax bill wasn’t passed until 2017, the CBO study doesn’t include its effect. Neither does this column. Still, it would cut taxes for wealthier Americans.)

All the numbers seem complex and confusing. Piercing the statistical fog is essential to anchor our debates in reality and not in journalistic or political mythology. It may seem that, except for the fortunate few, hardly anyone is getting ahead. That’s convenient rhetoric, but it just ain’t so.

This article was published in Investors Business Daily on 11-19-18. Robert J Samuelson writes about business and economic issues for the Washington Post.