Strategas’s Jason Trennert has pointed out over the years that ADP, a payroll processing company, produces at no cost to the taxpayer an extraordinarily thorough accounting of U.S. employment before the Bureau of Labor Statistics does. ADP is very much in the business of knowing what the BLS spends hundreds of millions to know.

This column has pointed out that Visa produces endless reports on consumer spending, borrowing, levels of debt, debt in arrears, etc. Well, of course it does. As a credit card company, there’s a reason for Visa to know these things, and to know them as far in advance as possible. Translated, Visa doesn’t wait for the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis to calculate consumer spending. Neither do sophisticated investors. Bank on it.

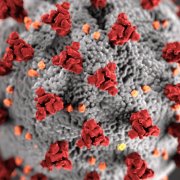

All of this should offer a clue to readers of something that’s not been said enough over the last several months. Markets don’t wait. The new coronavirus was a news item in January. It was known then that the virus had originated in China. U.S. companies derive enormous amounts of sales from the very Chinese customers who produce so much for American consumers. To export is to import, by definition. This is a long, or short way of saying that investors had a good sense long before politicians panicked in March that irrespective of the growing alarmism among politicians and doctors, the virus wasn’t terribly lethal. If it had been, there’s no way that U.S. equity markets would have reached all-time highs in late February. Again, markets don’t wait for politicians to respond, nor do they wait for doctors and entities like the CDC.

This truth brings to mind what Ken Fisher routinely tells audiences he speaks to. What you know, assuming it’s true, is already priced. Markets are relentless processors of information, good and bad. What you think, or what someone told you at a party to think is, if valid, already processed.

This is worth a thought in consideration of the growing investor focus on “volatility.” As the Wall Street Journal’s Gunjan Banerji explained it on Saturday, “In recent years, volatility has gone from a specialty of derivatives traders to a vehicle for trading in its own right. Investors big and small are wagering hundreds of billions of dollars on volatility.” Call it the politics trade.

Volatility speaks to big lurches in market sentiment rooted in surprise. Since markets are on their own feverishly processing information, it’s not as likely for the day-to-day vicissitudes of life to produce too much surprise. Markets yet again don’t wait, so it’s logically true that “news” about unemployment, shrunken sales, mild or lethal viruses, and reduced production in Bangalore is already known and priced well ahead of when we read about these things in newspapers.

To offer up yet another example, former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan was known to call FedEx CEO Fred Smith with great regularity. To export is to yet again import, so Smith has a keen sense of global economic activity based on shipments, and well before official figures are released.

Notable about Smith, and as was pointed out here a few weeks ago, his company has a big, 907 employee operation in Wuhan. Smith knew long before the hideous lockdowns that the virus had thankfully not killed any of his Wuhan employees. Had it proved extraordinarily lethal, we consumers of news would have known this truth long before March given the exposure of all-too-many public companies to China, along with Wuhan, the virus’s epicenter. These realities, good or bad, would have reached equity prices first, only for them to reach newspapers and news organizations after. Professional investors are paid not for being late to information, but for being early. That there was no market alarm in January or February about the coronavirus should once again have readers wondering….

Bringing it back to the Journal’s Banerji, he contends that markets “were once dominated by bulls who thought stocks would go up and bears who thought they would go down.” Investors focused on volatility don’t much care about the direction of shares as much as they care about big movements. In short, volatility traders are focused on politics.

Politicians are the wildcard. Way-too-powerful responders to news that markets have already processed, their responses to information that investors have been pricing for a lot or a little time helps create the volatility that is increasingly a trade. Because politicians are powerful, their decisions have economic impact.

But since politicians are members of the human race, it’s not always predictable what they’ll do. If it were, or if their power was limited, they couldn’t create volatility. Unfortunately, it’s neither true that their actions can always be known in advance, nor is it true that their power is so hemmed in that their actions don’t matter.

Which to a high degree explains volatility. Big market movements are a function of surprise, and politicians responding to yesterday’s news create the surprise.

Imagine then, the economic growth lost to the volatility trade that is in so many ways a politics trade. Think how much further along the global economy would be if hundreds of billions weren’t directed toward hedging the volatility of statesmen, and instead toward the ideas and businesses that drive progress. Most of all considering the troubled present, imagine where the global economy would be today if politicians had listened to the markets over their own, highly emotional and vain, selves.