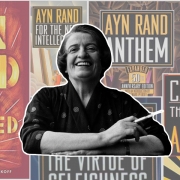

The previous blogpost of Why Ayn Rand Laughs explored two concepts of justice (moral sanction and penal codes), and two examples of productive virtues not justly rewarded. Because justice is a function of law and culture, its dominant philosophy will affect its application. Because productiveness is a function of individual volition, the dispensing of justice may influence each person’s choices for action or inaction. Rand tells us in Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal, that when cultural mores promote envy we get,

The penalizing of ability for being ability, the penalizing of success for being success, and the sacrifice of productive genius to the demands of envious mediocrity.

In her 1943 novel The Fountainhead, Ayn Rand examines the action of two characters, and their treatment by those who wield justice in a world that lionizes mediocrity. The one who values creative independence, the one who pursues the mediocrity of conformity, and the ultimate rewards for each.

The Moral Sanction of Mediocrity

The novel’s architectural art hero, Howard Roark, declared “I don’t build in order to have clients, I have clients in order to build.” In today’s headlines, Bernie Madoff is the exemplar of the mediocrity who built in order to have clients. In his case, it was a colossal financial pyramid. Structurally, a pyramid is very sound. As it rises, the weight pushing down from above gets lighter, and is dispersed over the layers below that are wider and stronger. One attribute of a mediocrity is that they avoid reality, and Madoff’s pyramid quickly became inverted.

Ayn Rand defines it in her 1970 essay The Comprachicos, “Mediocrity does not mean an average intelligence; it means an average intelligence that resents and envies its betters.” The root of Madoff’s envy was the unassailable integrity of free markets. His early career was rooted in building stock trading businesses designed to “beat the market.” His success led to him becoming a highly respected industry leader, and then board chairman of the National Association of Securities Dealers, the self-regulating body of the US over-the-counter stock market.

This is where Madoff reached the pinnacle of his personal pyramid, a recipe for disaster described by Rand in Chapter 12 of her epic novel, Atlas Shrugged, titled the Aristocracy of Pull. Now able to leverage his political influence, he quietly attracted thousands of wealthy investors to his investment management business, and inverted his pyramid.

The scheme was simple, develop a reputation for delivering consistent, above-market returns (even during extreme markets) by printing bogus monthly statements, and fund the gains with capital from new suckers seeking Madoff’s market-beating Midas touch. This is where his subjective morality met his barren creative talents.

As Rand explains, “A creative man is motivated by the desire to achieve, not by the desire to beat others.” Yet most of his clients turned a blind eye to the absurdity of all this. They had never learned that “The verdict you pronounce upon the source of your livelihood is the verdict you pronounce upon your life.” They did not know or respect money.

The Selfless Second-Hander

Madoff was not a selfish man, he was utterly selfless. He had to maintain this superficial veneer as the all-knowing insider, at all costs. He did not own his life, conformity owned him. This is precisely how Rand’s Fountainhead character, Peter Keating, derived his own self-respect – from others (second-handedly). The object of his envy was the unassailable integrity of his classmate, Howard Roark. The novel begins with Keating graduating with top honors from architecture university after Roark had been expelled for refusing to copy classical designs.

Upon graduation, Peter Keating’s career blossomed when he was hired by a prominent architectural firm. This is where his own subjective morality and barren creative talents met. As a result, he secretly consulted his college buddy Roark to help him with complex design problems. Much like Madoff refused to understand the nature of free markets, Keating didn’t understand the nature of buildings with integrity, and asked Roark,

Do you always have to have a purpose? Can’t you ever do things without reason, just like everybody else? You’re so serious, so old. Everything’s great, significant in some way, every minute, even when you keep still. Can’t you ever be comfortable-and unimportant?

Rand answers Keating’s question in another context, in The Comprachicos,

Observe also the intensity, the austere, the unsmiling seriousness with which an infant watches the world around him. If you ever find, in an adult, that degree of seriousness about reality, you will have found a great man.

Peter Keating is eventually broken by the mediocrity worship and persecution of excellence that he endorsed. A wealthy investor offers him a commission in exchange for his wife, his public sponsor convinces him to testify in court against Roark, and he loses everything he held dear. Except his empty soul, as did Madoff.

Integrity, or the Public Good

Bernie Madoff is now a reviled figure. After all, mediocrities are commodities to be tossed aside when they no longer serve the “the public good.” As Rand reminds us, “If a businessman makes a mistake, he suffers. If a bureaucrat makes a mistake, you suffer.” This moral code is why Madoff’s pyramid scheme is more popular than ever, and known as Social Security. The difference is that government’s new “investors” contribute under penalty of law. But this pyramid is also inverted – the weight of increasing beneficiary payments is getting heavier, and its supporting base of contributions is getting smaller.

Social Security recipients are rightfully recouping the assets that were confiscated from them, regardless of how those benefits are funded. But those promoting the success of government “insurance,” because millions are dependent on it, are merely giving the Chamber’s small business growth award to the local crack dealer. These mediocrities who choose progressive political, education and journalism careers are today’s version of the medieval Comprachicos.

Instead of physical deformities, they stunt intellectual growth, produce Keatingesque second-handers, and imprint social justice and environmentalism on young minds as their moral purpose, not their own happiness. As Ayn Rand warns in her 1971 essay The Age of Envy,

It is not equality before the law that they seek, but inequality: the establishment of an inverted social pyramid, with a new aristocracy on top—the aristocracy of non-value.

This is analogous to Victor Hugo‘s classic novel The Man Who Laughs, except that envy is the progressive tool, mediocrity is the ideal, and conformity is the goal.