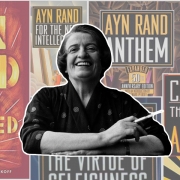

You can have your cake and eat it too; so say Soviet authorities in 1920’s Russia. Just not today. The Party needs the cake, and will be consuming their share of it first. The consolation prize for patience is lice infestation, literally it’s free; figuratively, not so much. This describes the package-deal offered to the human cattle in Chapter 1 of Ayn Rand’s 1936 novel, We the Living.

As they arrived in Petrograd riding boxcars from Crimea in the south, Alexander Dimitrievitch Argounov and his family were among them. Appearing first is the determined, idealistic, and naive 18 year old (and 1920 Russian Gen Z’er) daughter Kira, “with the defiant, enraptured, solemnly and fearfully expectant look of a warrior who is entering a strange city and is not quite sure whether he is entering it as a conqueror or a captive.”

Our We the Living Study Group accepted the challenge of understanding this important novel last week, and Chapter 1 presents a sharp contrast between Kira’s optimism and the despair of her family and their fellow travelers. Lurking in the shadows of the Facebook private forum, Doctor J explains and gives us a modern example,

She could not relate to shallowness. It’s OK to miss things, but obsession can lead to depression and suicide in challenging times. I miss root beer barrel candy but it’s not something I need to be talked off the ledge for, though the Beer Police in Central Planning (Congress) are working on outlawing that.

The absurdities of socialism are presented immediately in We the Living, “From the border of Poland to the yellow rivers of China, the red banner rose triumphantly to the sound of “Internationale” and the clicking of keys, as the world’s doors closed on Russia.” While humor is a great weapon for maintaining dignity in the face of brutality, it’s not easy to find, but here Rand inserts a little sarcasm and irony,

“Could you please step out for a moment, citizens?” Two gentlemen were were traveling comfortably in that private little compartment, one of them on the seat, the other stretched in the filth on the floor. Left alone where no one could watch, the lady in the fur coat unwrapped a little bundle of oiled paper. She had a whole boiled potato.

This economic system, known affectionately in 2020 America as Democratic Socialism, is what leads to the cherished equality of a train toilet becoming a private dining room. Thankfully, it is expertly explained by a passenger as: “if you’re not a speculator, you’ll starve, but if you are, you can buy anything you want, but if you buy you’re a speculator, and then look out.”

Another way to illustrate this cognitive dissonance is the greeting the train passengers received upon arrival at Petrograd station in Chapter 2. The first banner read: Comrades! We Are the Builders of a New Life! The other banner read: Lice Spread Disease! Citizens, Unite on the Anti-Typhus Front! The comparative irony Rand presents with these is stunning – to be a comrade is to be lice, citizens are builders where building is forbidden, and life is defined as avoiding death.

The death avoidance premise also defines 2020’s progressive economic lock-down banners, We’re All In This Together! Flatten the Curve! Wear a Mask, Save a Life! Their consequence was “peaceful protests” in Democratic party strongholds like Minneapolis, Seattle, Brooklyn and Portland, which are now eerily similar to the scene witnessed on 1920’s Nevsky Prospect in Petrograd,

New signs were cotton strips with glaring, uneven letters. Gold letters spelled forgotten names on the windows of new owners, and bullet holes with sunburst cracks still decorated the glass. There were stores without signs and signs without stores.

One of those forgotten names was that of Kira’s uncle. “Vasili Ivanovitch spoke seldom. He said only: Is that my little friend Kira? The question was warmer than a kiss.” Here Ms. Rand gives us another glimpse into Kira’s character, it seems she adores her uncle Vasili. Much like Kira’s father Alexander, he was a self-made man, “his backbone had been as straight as his gun; his spirit as straight as his backbone.”

Independence is what commands Kira’s attention and respect, to a fault, and clarity is what Ayn Rand commands in her writing, to the vexation of her critics. Lurking in the corridors of our Facebook forum, Mama Bear relates one such experience while Reliving We the Living,

Ayn Rand’s description of worn and weary people is so realistic: such as the woman left at the train station with her eight children because there was no room in the box car. She really defines her characters and the era, many readers could not imagine that type of life.

The conversation continued with The Padre saying “we are able to personalize, through the Argounov family, what confiscation of private property truly means. The family is physically and emotionally devastated.” Except Kira refuses to be devastated, and most people cannot imagine the type of life she envisions.

In Chapter 3, Rand brings clarity by focusing on Kira’s childhood during the Argounova’s vacations at their summer residence. While the house faced their spacious, manicured lawn and gardens, it had its back to the side of the hill overlooking a river “like a mass of rock and earth disgorged by a volcano and frozen in its chaotic tangle.” Kira preferred to face reality, unconditionally, because there are none,

Kira was left alone to spend her days in the wild freedom of the rocky hill, as its undisputed sovereign. She swung from rock to rock, grasping a tree branch, throwing her body into space. She made a raft of tree branches and, clutching a long pole, sailed down the river.

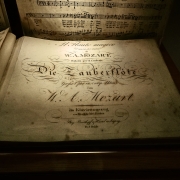

“Some enter life from under temple vaults, head bowed in awe. Some enter with a heart tramped, crying for the warmth of the herd. Kira Argounova entered life with the sword of a Viking pointing the way and an operetta for a battle march.”

She knew she had a life and it was her life. She knew the work she had chosen and which she expected of life. Her future was consecrated, because it was her future. Over Lydia’s bed hung an ikon, over Kira’s – an American skyscraper.