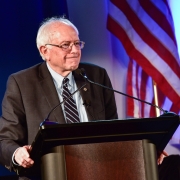

In the United States, thanks largely to Bernie Sanders, the term “single-payer health care” has become more or less synonymous with the phrase “universal healthcare.”

This stems partially from the fact that “single-payer” is the term most often used to refer to foreign systems of universal healthcare, and also because most Americans know virtually nothing about how foreign healthcare systems work.

Moreover, when it comes to interacting with foreigners, Americans most often encounter the writings and opinion of other English speakers — which mostly means Canadians and British subjects. And it so happens both Canada and the United Kingdom employ single-payer healthcare systems.

Elsewhere in the world, however, it is not uncommon to find other countries that employ “multi-payer” and “multi-tier” healthcare systems that are nonetheless designed to provide universal coverage.

This is also especially important to recognize because single-payer healthcare systems are some of the worst systems in regards to freedom of choice and healthcare quality. This is because the primary benefit of single-payer healthcare — as so often recounted by its supporters — is that it is cheap.

But “cheapness” is not exactly the best criteria for judging a healthcare system, and the shortcomings of single-payer systems make this abundantly clear.

What Is Single-Payer?

So what makes a single-payer system distinct from other systems? As the name implies, a single-payer system is one in which there is only one source of payments or funding for healthcare transactions. This source, of course, is the government.

So, in a single-payer system healthcare services is paid for only through government funding. This can be done through a variety of mechanisms. For example, healthcare facilities can be directly funded and run by government agencies or they can be nominally private providers which receive all their payments from a government agency.

With single-payer systems there is no competition from other “payers” such as private insurance companies, or even cash-for-service firms.

Exceptions can be found in those services that are not deemed to be “essential” healthcare services. In Canada, for example, private health services are allowed in services legally defined as non-essential such as mental health, pharmaceuticals, some types of eye care, and long-term care.

Thus, strictly speaking, no system is a “pure” single-payer system that encompasses every conceivable type of care. Consequently, in both the UK and Canada, one will still encounter activists who think that the state-run healthcare systems are too laissez-faire. These critics claim coverage should be expanded to exclude private competition even more, and to expand the definition of “essential” services. It is not uncommon to hear claims that these systems are becoming “two-tier systems” (meant pejoratively) in which the implication is that there is one low-quality tier for ordinary people, and a high-quality tier for everyone else.

In practice, however, there is a reason most of the world points to the United Kingdom and Canada as examples of single-payer systems: they offer very few private-sector options for core services. While there are always some areas where private-sector activity allowed, these systems are fundamentally built on the idea of excluding private competition and private payments in favor of directly controlling healthcare prices and services.

What Are the Multi-Payer Systems?

In contrast to a single-payer system, numerous countries with universal healthcare systems employ multi-payer systems.

In the case of Germany, there are multiple statutory tiers of healthcare. Most Germans below a certain income level are covered by a main tier of heavily-subsidized health care. But service providers are not government owned, and they compete for customers at all income levels, including those who use private insurance.

Switzerland, meanwhile, employs a private-sector-based insurance mandate similar in some ways to Obamacare in the US. That is, the Swiss are required by law to purchase health insurance or face legal penalties. Low-income Swiss receive subsidies to purchase insurance. The Swiss system also allows for small fees to be paid by patients at each doctor visit, up to an annual maximum.

A key difference between US and Swiss insurance mandates, however, is that Swiss health insurance is purchased at the individual level, and not through employers.

These multi-tier systems — which also include France and the Netherlands, among others — are not free-market systems, of course. In all cases, markets are heavily regulated in terms of mandates that providers cover pre-existing conditions. Other regulations are used in attempts to control costs.

Single-Payer: Bad for Both Freedom and Quality

Indeed, the drive to control costs is a central reason for the single-payer healthcare system. By outlawing competition for many procedures, and by making healthcare providers dependent on a single governmental payer, it becomes easy for governments to force down prices by limiting payments to providers, and by dictating what sorts of treatments will be allowed.

But the ability to force down costs is not necessarily a great measure of a healthcare system’s desirability.

A “cheap” healthcare system can certainly be achieved by imposing price controls, and cutting out pricey treatments deemed un-economical by state bureaucrats. But this often results in long waiting times and loss of quality. Not surprisingly, wait times for treatment have been shown to be significantly longer in Canada than in Germany, Switzerland, and France.

Moreover, by prohibiting competition in core services, providers lack an economic incentive to improve the quality of care. As noted by the UK’s Civitas organization, competition among providers — even in a heavily regulated and subsidized systems — is important to encouraging quality services. Referring to the German system, the Civitas researchers note:

Competing providers usually treat all patients but have an incentive to attract the high paying privately insured.This has a ‘levelling up’ effect on the quality of care available to all.

Similar dynamics are true in Switzerland, and even in Denmark where the state encourages competition between hospitals. In the UK, on the other hand, the state-controlled National Health Service has no reason to improve or innovate outside of public outrage. As George Pickering has noted, quality in the UK has become an increasing concern with honest observers of the British healthcare system. One recent open letter from British physicians to the Prime Minister further noted that it had become “routine” for patients to be left on gurneys in corridors for as long as 12 hours before being offered proper beds, with many of them eventually being put into makeshift wards hastily constructed in side-rooms. In addition to this, it was revealed that around 120 patients per day are being attended to in corridors and waiting rooms, with many being made to undergo humiliating treatments in the public areas of hospitals.

Yet, apparently unaware of how other systems function, many British voters continue to support the British single-payer system uncritically. Pickering continues:

the characteristics of the NHS [i.e., universal coverage] which Britons mistakenly believe to be a unique source of pride, are actually present in almost every other healthcare system in the developed world; yet these other systems lack the NHS’s hostility to innovation in medicines and practices. Furthermore, the high number of avoidable infant deaths in some of its trusts led to the NHS being brought under government investigation in April for standards of maternal care which regulators described as “truly shocking.”

The High Cost of Government Price Controls

By allowing providers to compete, it’s harder for governments to control costs. Thus, it’s not surprising that when it comes to government spending on healthcare subsidies, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Denmark are among the big spenders. In both Denmark and the Netherlands, about one-third of the population chooses to buy private insurance. (In Switzerland, of course, the system is based on mandatory private insurance.) Prices are thus bid up as a result, for both government and the private sector.

But, taxpayers and healthcare consumers also get what they pay for.

While multi-payer systems often tolerate higher prices in the name of better choice and higher quality, single-payer outlaw choice in the name of “savings.”

Defenders of single-payer systems will justify these roadblocks to high-quality service as essential for maintaining “fairness.” As Canadian historian Ronald Hamowy has noted, there has been opposition in Canada to allowing even small clinics performing diagnostic services like MRI scans. This, it was argued, would allow rich people to “jump the queue.”

The message is thus this: either you get healthcare services on the government’s terms, or you don’t get it at all.

Comparisons with the US System

Politicians in the US are increasingly willing to force markets toward some sort of universal health system. This certainly has its downsides, but the most alarming aspect of the current drive is the fact many of the loudest voices for universal healthcare are insisting on single-payer healthcare as the only alternative.

But, if US policymakers are going to continue to move the US healthcare system even further away from functioning markets, less damage would be done by avoiding a single-payer system and instead embracing a multi-payer system.

After all, the US is already a non-universal multi-payer system, and the US already has a system that heavily subsidizes healthcare through programs like Medicaid and Medicare. In fact, nearly one-half of all healthcare spending in the US is already paid by governments. And one-third of Americans already receive healthcare through some sort of government program.

Transitioning to a universal healthcare system is going to be costly — in terms of dollars — no matter what. But by adopting a single-payer system, Americans would be forced to endure high costs that aren’t calculated in dollars: long wait times, rationed care, and few choices beyond the government-controlled system.

The innovation, quality improvements, and timely care offered by competing private firms would be largely destroyed by adopting a single-payer system. Although these advantages have been only partially preserved by multi-payer systems that allow some of the advantages of a free marketplace, those now clamoring for a single-payer system would have us believe this all must be abolished in favor of near-total government control.

Ryan McMaken (@ryanmcmaken) is a senior editor at the Mises Institute.