You see, Harris’ cult is the “cult of the Presidency.” Coined by Gene Healy, the phrase describes the worship that so often accompanies what many Americans consider to be a grand, magisterial office from which all good things flow, and all evil seeks to corrupt. In their peculiar astronomy of this mindset, the Oval Office occupies the center of the universe. Everything revolves around it.

Congress Who?

The Presidency is a jealous god. It tolerates no competitors to its power. And neither does Kamala Harris.

Over the course of her campaign, she has repeatedly promised to bypass Congress and take unilateral action on a whole host of intensely divisive issues. On immigration, she has vowed to issue an executive order granting citizenship to “Dreamers” (migrants brought to America illegally by their parents). On the environment, she says she will declare a “state of water emergency” and force the country to re-join the Paris Climate agreement. She also wants to ban the use of fracking.

Many observers have noted how dictatorial these statements sound, and rightly so. To follow through on any one of these proposals would be deeply suspect, but the sheer number of them, coupled with Harris’ brazenly peremptory attitude, must leave no doubt as to her authoritarian ambitions.

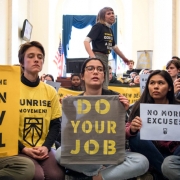

For Harris, Congress is at best merely an advisory body. As a kindly gesture, the President may ask Congress for permission to do something, but he or she does not really require their assent. During a CNN town hall, Harris said she would deliver an ultimatum to Congress on gun control:

[U]pon being elected, I will give the United States Congress 100 days to get their act together and have the courage to pass gun safety laws. And if they fail to do it, then I will take executive action. And specifically what I’ll do is put in place a requirement that for anyone who sells more than five guns a year, they are required to do background checks when they sell those guns.

Essentially, Harris would ask Congress to rubber-stamp her gun-control policies in order to give them the appearance of legitimacy. But if they refuse to comply, she can simply forgo such formalities.

At worst, Congress is a frustrating (and ultimately vestigial) obstacle to Harris’ domestic policy goals. They have, for example, stubbornly failed to pass the “Green New Deal,” a massive government-enforced overhaul of the economy intended to fight climate change. Should they continue to remain idle on this issue, Harris warns, she will get rid of the filibuster. How she plans to do this is unclear: the filibuster is an internal Senate procedure and therefore not constitutionally subject to presidential decree. But the Cult of the Presidency knows no limitations.

The Constitutional Road Less Traveled

Harris’ attitude is unfortunately emblematic of America’s obsession with the presidency. We have become accustomed to organizing society around the president, whoever it may be. If the stock market goes up, we praise the president; if it goes down, we criticize him. When there’s a natural disaster, we expect the president to be directly involved in the relief efforts. When there’s a mass shooting, we expect him to visit the survivors and memorialize the victims.

Our society’s obsession with the president is both a cause and a consequence of his immense power. Public policy today is almost exclusively directed from the Oval Office and so of course we end up paying a lot of attention to the chief executive.

But at the same time, this cult-like attention helps to feed the behemoth that is the imperial presidency. After all, everyone can name the president, but very few know who their own congressional representative is. Fewer still can name the Speaker of the House. It is only natural, then, that folks look to the president for everything: he is often the only national political figure they are even remotely familiar with.

On a practical level, many of Senator Harris’ political ilk have acquiesced to the use of executive power simply because it’s the easiest way to get things done. Unlike the hyper-partisan “do-nothing” Congress so often derided by Harris, the president, by virtue of being a single person, is not hampered a lack of consensus. If left unimpeded by a passive Congress and deferential courts, the president as head of the executive branch may simply enforce the nation’s laws in any way he pleases. Under these circumstances, it should come as no surprise that presidents are increasingly pushing their luck and creating new laws unilaterally.

On the other hand, Harris is deeply critical of how President Trump has been governing. But rather than lead a fight from the Senate to reassert the authority of Congress, and thereby limit the damage a bad president can inflict, as she certainly could, Harris has been campaigning to increase the president’s power. Her main critique is not that the president is too powerful, but merely that the wrong person is in office.

The cult of the Presidency is getting stronger and the Constitution is getting weaker. And that should concern us all.