LOS ANGELES—Arianna Williams spends 90 minutes each way riding the bus about 10 miles to her job in a hair salon.

The commute is particularly frustrating when she considers about how long it would take by car: about half an hour

“It’s crazy, the number of times I’ve been on the bus and thought, ‘I could’ve been there three times by now,’” the 36-year-old said while inching along Wilshire Boulevard, one of Los Angeles’s largest thoroughfares, on a recent morning.

Bus ridership in America’s second-largest city is plummeting as more commuters, fed up with journeys that can be painfully slow due to frequent stops and indirect routes, use growing incomes from the healthy economy to buy a car. The switch saves them time but worsens the overall traffic that buses are caught in, making buses even less appealing to the remaining riders.

There were about 276 million total bus rides in the system run by the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority, known as LA Metro, last year. That is down 24% since 2013, significantly bigger than drops in public-transit usage in other major cities like New York, Chicago, Denver and Phoenix. Ridership on L.A.’s rapidly expanding but significantly smaller rail system declined 5% in the same period.

The drop is particularly tough news for city leaders to swallow given that LA Metro is in the midst of a 40-year, $120 billion expansion project, funded by a sales-tax increase passed in 2016. The measure was meant to alleviate the region’s long-overcrowded roads that cause the average Angeleno to spend more time in traffic than do drivers in any other city—about 119 hours in 2017, according to a recent study by Texas A&M University.

“It’s too easy to drive in this city,” said Phil Washington, the chief executive of LA Metro. “We want to reach the riders that left and get to the new ones as well. And part of that has to do with actually making driving harder.”

Ride-sharing services operated by Uber Technologies Inc. and LyftInc. have only made it easier for people to keep traveling in cars, though the services remain cost-prohibitive for many working-class commuters.

Enabling buses to avoid traffic and reach destinations faster than cars is the most important step needed to turn around the ridership decline, said Conan Cheung, who is leading a study for LA Metro expected to be completed next year. The results of the study could lead to the first major overhaul of bus routes in 25 years.

The easiest way to make buses faster, experts like Mr. Cheung say, is to give them their own dedicated lanes on busy roads. A high-speed bus lane in the city’s San Fernando Valley has been one of LA Metro’s few success stories in recent years.

LA Metro’s CEO says bus-only lanes are needed to help change behavior in a city whose culture is largely built around driving. But selling communities on bus-only lanes has been difficult, as car owners oppose steps that would make roads slower for them and for drivers who shop at local businesses.

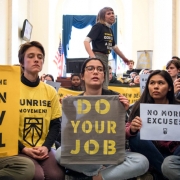

At a meeting this month in the Northeast L.A. neighborhood of Eagle Rock, residents booed when a Metro representative mentioned a proposal for a “bus rapid transit” lane. Some held up signs saying “save the trees,” a reference to medians that might be eliminated, while others passed out pamphlets accusing LA Metro of corruption.

“Eagle Rock is flourishing,” said Divina Lombardo, one of hundreds of people who turned out in opposition. “The people coming here won’t come because of the buses and construction.”

Mr. Washington said bus lanes like the one proposed in Eagle Rock are just one of numerous steps needed to change behavior in a city whose culture is largely built around driving.

The city is also expanding a rail system that currently serves only a fraction of the city. The process has been slow, however. While LA Metro has held public hearings to develop a rail system to help alleviate traffic on the notoriously clogged I-405 freeway that connects the San Fernando Valley to L.A.’s west side, there aren’t any concrete plans yet.

In addition, Mr. Washington is also pushing for congestion pricing, similar to that used in cities like London, which would impose charges for driving cars in crowded neighborhoods at peak times. Proposals for a pilot congestion-pricing program in L.A. have yet to gain much political traction.

He said he also wants to explore partnerships with the private sector. Public-private partnerships encouraging workers to take public transit have helped Seattle buck the national trend and increase bus and rail ridership 11% since 2009, according to the city’s transit authority.

Passengers wait to board a bus at Patsaouras Transit Plaza at Union Station in L.A.

Those types of changes would require a shift in many Angelenos’ attitudes toward the road, which Mr. Washington said city leaders need to try to make happen.

“Sometimes you have to tell people what’s good for them,” he said.

Meanwhile, many Angelenos are doing the exact opposite of what Mr. Washington would like. Hugh Brockington, a musician who lives in the L.A. suburb of Pasadena, rode buses to auditions all over the city after his car was repossessed two years ago. But they were often so slow he realized he could travel faster by bike. Since showing up to auditions sweaty wasn’t an option, however, the 34-year-old saved his money and bought a car again.

“I just couldn’t do it anymore,” he said of the frustration of riding buses.

This article appeared in wsj.com on Aug 25, 2019