America in 2020, along with a few other mostly Western countries, is the most free, tolerant, and prosperous society the world has ever known. In the annals of human history, it is a very recent phenomenon. The incredible technological advances we take for granted, especially the extraordinary computer in the palm of your hand right now, would be impossible without the personal liberty that preceded it.

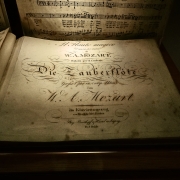

From Ludwig van Beethoven’s “heroic” period in the early 19th century, to the cowardly murder of Prince Ferdinand (by a Bosnian Serb terrorist from The Black Hand) in the early 20th century, humanity experienced the greatest surge we had ever known. The 19th century’s self-creation was morally superior, its capitalism was socially and economically superior, and its Romantic art was ethically superior, yet the 19th century’s dominant philosophers paved the way for World War I and Stalin’s Great Terror.

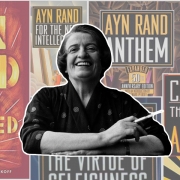

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that helps us comprehend and resolve this contradiction because it addresses man’s relationship with the rest of the natural world. According to the Ayn Rand Lexicon, metaphysics is,

That which pertains to reality, to existence. Any natural phenomenon – any event which occurs without human participation, is the metaphysically given. It could not have occurred differently or failed to occur.

The philosophers of the 19th century who influenced the events of the 20th century were, among others, Immanuel Kant (“From such a crooked wood as that which man is made of, nothing straight can be fashioned”), Georg Hegel (“To him who looks upon the world rationally, the world in its turn presents a rational aspect. The relation is mutual”), and Karl Marx (“Our mutual value is for us the value of our mutual objects. Hence for us man himself is mutually of no value”).

In other words, people are inherently evil, the reality of the world is subjective, and self-sacrifice is our highest calling. As asserted by journalist and filmmaker Peter Savodnik in Woke America is a Russian Novel,

The metaphysical gap between mid-19th-century Russia and early-21st-century America is narrowing. The parallels between them then and us now, political and social but mostly characterological, are becoming sharper, more unavoidable.

The literary characters he uses are from Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, Turgenev’s Father and Sons, and Chernyshevsky’s What Is to Be Done, and Savodnik cites them as far-reaching examples of the philosophical conditions that culminated in the Russian Revolution,

The moment, or series of moments, when the language of nihilism and death acquired a certain currency and the possibility of the end of the old order came into focus.

In 2020 America, the language of nihilism is politically correct speech, whose politics is multiculturalism, and its metaphysics is egalitarianism – the equality of everyone’s choices and character. All of this negates human volition, aka free will. It presupposes our values, choices, and fate are predetermined at birth, and assigned to us by our political identity group. As Savodnik continues,

The similarities between past and present are legion: The coarsening of culture, the opportunism and fecklessness of so-called elites, the corruption of institutions, the ease with which Bernie Sanders’ romanticizes political revolution.

In her 1936 novel We the Living, 20th century Russian novelist Ayn Rand bridges the gap, and creates a fictional scene depicting the Russian Revolution’s White army surrender to the Reds at Melitopol in 1920,

Comrades! Let me greet in you the awakening of class consciousness! Another step in the march of history toward Communism! Down with the damn bourgeois exploiters! Loot the looters, comrades!

Class consciousness is fealty to your political identity group, Communism is the negation of human volition, and the bourgeois exploiters are the manufacturers and merchants who produce every material need and desire for human prosperity. But when a culture’s dominant philosophy becomes malevolent, and motivated by envy and fear, force replaces reason and trade is conducted by blood instead of money. Here, Savodnik describes the mindset needed to survive this metaphysical death premise,

Only idiots worried about the truth. There was no truth. What was most important was to keep one’s head down and, if need be, accuse wantonly. Accuse! Accuse! Accuse! Or as Americans like to say, the best defense is a good offense. Until all that was left was the pathetic, bloodless corpse of a country dislodged from itself.

We the Living dramatizes the Benevolent Universe Premise, aka the life premise. In her non-fictional The New Left, Rand defines this as “a fundamental conviction which some people never acquire, some only hold in their youth. The conviction that ideas matter, that knowledge matters, that truth matters, that one’s mind matters.” In his article Justice in a Benevolent Universe, philosopher Onkar Ghate expands on this theme,

You must have a clear and sacred devotion to your own mind and life and to the inexorable requirements of reality. Through the heroine Kira Argounova, Rand depicts the nature of this metaphysical conviction. And in an ending of astonishing beauty and power, the story shows what it looks like to remain untouched, to the end, by the evil of one’s surroundings.

To that end, we cordially invite you to consider the We the Living Study Group on Facebook, join a unique group of active minds in our online forum, and awaken the soul of your childhood. The conversations will begin the week of August 2nd and cover Chapters 1 – 3. The weekly calendar for reading, questions, and commentary is posted in the About section of the group page. Sign up for our discussion group! The online forum is private, and the conversation is meant to be engaging, polite, and productive!