He is a lawyer who thinks there are too many lawyers and too much law, and that both surpluses are encouraged by misbegotten ideas about ideal governance. One such idea is that ideal governance is a sensible aspiration. In the Yale Law Journal (“From Progressivism to Paralysis”), he explains why “Covid-19 is the canary in the bureaucratic mine.” Modern government “is structured to preempt the active intelligence of people on the ground. This is not an unavoidable side-effect of big government, but a deliberate precept of its operating philosophy. Law will not only set goals and governing principles, but it will also dictate exactly how to implement those goals correctly.” Result: paralysis. Governance congeals because “the complex shapes of life rarely fit neatly into legal categories.”

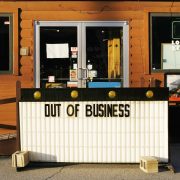

The proportion of lawyers in the workforce almost doubled between 1970 and 2000, and the nation now is, Howard has said, ludicrously dense with laws and dazed by “rule stupor.” Constructing the Empire State Building took 410 days in the Depression. The Pentagon took 16 months in wartime. In this century, however, nine years were consumed just with permitting for a San Diego desalination plant. Five years and 20,000 pages of environmental and other compliance materials preceded a construction project (raising the roadway on New Jersey’s Bayonne Bridge) with almost no environmental impact.

Then the pandemic arrived. Red tape prevented public health officials from using tests they possessed or buying tests overseas. To function, hospitals had to jettison myriad dictates about restrictions on telemedicine, ambulance equipment and many other matters. To get federal funding for school meals transferred to providing meals during summer months, 50 formal waivers were required from the states. And, Howard writes, “the bureaucratic instinct was relentless even when waiving rules. Each school district in Oregon was first required ‘to develop a plan as to how they are going to target the most-needy students.’ ” Meanwhile, needy children were getting no meals.

Protesters take to the streets, Howard says, on the naive assumption that “someone is actually in charge and refusing to pull the right levers.” If only. “From the schoolhouse to the White House,” Howard says, “public officials are disempowered from making sensible choices by a bureaucratic and legal apparatus” that stipulates “the one correct way” to achieve goals.

Granularity of regulation is, Howard believes, the fruit of the Progressive Era’s goal of neutral government, purified and professionalized and “untainted by the judgments of imperfect humans.” To this chimera, add encyclopedic contracts with public employee unions that insulate their members from accountability. When California can dismiss for poor performance only two of about 300,000 public school teachers a year, even mere mediocrity is optional. The Minneapolis policeman who suffocated George Floyd had been the subject of 18 complaints, but his supervisors had no practical way to terminate him. The 2,600 complaints against Minneapolis officers since 2012 resulted in 12 officers disciplined.

The Progressive Era dream — purging human judgment from public choices; eliminating human agency from the implementation of public decisions — is today’s nightmare. Government accountability now means, Howard writes, only court-enforced compliance with “the ever-thickening accretion of rules, rights, and restrictions.” So, “slowly but inevitably a sense of powerlessness” pervades public and private institutions.

The Progressive Era project that began 120 years ago got its second wind 60 years ago. But “no experts back in the 1960s,” Howard writes, “dreamed of thousand-page rulebooks, ten-year permitting processes, doctors spending up to half of their workdays filling out forms, entrepreneurs faced with getting permits from a dozen different agencies, teachers scared to put an arm around a crying child.” The quest for “a government better than people” advanced because bureaucracies became “preoccupied with avoiding error without pausing to consider the inability to achieve success.” A virulent, fast-moving and mutating virus is teaching the cost of this.