Why Soaring Inequality Is The Greatest Enemy Poverty Has Ever Known.

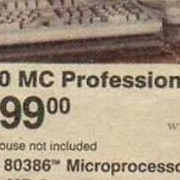

In 1989 then prominent computer maker Tandy released the Tandy 5000. Though the poorest of today’s poor would haughtily turn their noses up to the 5000 today, at the time this “most powerful computer ever!” was rather expensive. Try $8,499 (mouse and monitor not included) expensive. Nowadays one can buy a brand new Hewlett-Packard computer that’s exponentially more powerful than the 5000 for $200 (no monitor needed, mouse included) at Best Buy, not to mention computers that perform quite a bit better for not much more at any Apple Store or at Dell.com.

The nearly $9,000 “most powerful computer ever!” came to mind while reading New York Magazine writer Eric Levitz’s latest “damning indictment of capitalism.” What has Levitz worked up is that the richest 1 percent have increased their wealth to the tune of $21 trillion since 1989. To say that Levitz lacks nuance, or feel when analyzing numbers, brings new meaning to understatement. The simple plainly confuses Levitz. We know this because simple explains soaring ‘1 percent’ wealth: thanks to technological advances hatched by 1 percenters past and present, the strikingly talented can meet the needs of more and more people around the world. So shrunken by technology is the world in the figurative sense that it’s almost as though Jeff Bezos lives next door to all of us in terms of his ability to serve us.

After that, as a look at just about any wealth list from 1989 would make clear to the mildly sentient of today, the “1 percent” at the end of the 20th century’s penultimate decade in very few instances resemble the 1 percent of today. With wealth, the team picture is constantly changing as innovators of the present replace yesterday’s. The previous truth explains why what gives the ultra-sensitive Levitz anxiety is in fact a sign of immense progress. Thank goodness the “1 percent” have seen their wealth increase $21 trillion. It’s a logical signal of rising living standards for everyone, not rising poverty as Levitz laughably concludes.

For readers to understand why, they need only consider yet again the “most powerful computer ever!” that came out the year that Levitz cites as the one that began the “damning indictment of capitalism.” Computers then were not very friendly, or usable, or even accessible. Few had them. They were too expensive. Does anyone remember the “internet cafes” of the early 2000s in which we’d rent internet and computer time? Nowadays Apple computers are seen by many as the luxury pricepoint computers of the moment, yet they can easily be had for not much more than $1,000. How lucky we all are that the late Steve Jobs revived Apple, and that Michael Dell mass produced excellent computers that are even cheaper than those made by Apple at his eponymous computer company. In defense of Tandy’s $8,499 5000, it seemed cheap relative to initial mainframe 360 computers marketed by IBM in the 1960s, and that set buyers back well over $1 million.

Considering something as basic as a phone call, one made on a landline phone back in 1989 was going to be very costly assuming the call recipient wasn’t nearby. In 1989 a call from Dallas to Ft. Worth was going to be expensive, New York to Los Angeles very expensive, and New York to London almost unthinkable unless you were very well-to-do. “Long distance call” is a descriptor of something that’s no longer a factor, but it wasn’t too long ago that expensive “long distance calls” (ssssshhh) were made from the office….Crucial here is that these calls took place on landlines simply because in 1989 mobile phones were so rare that the sight of them generally caused people to stop and gawk. Mobiles were the exceedingly obscure gadgets of movie producers in Beverly Hills and New York LBO specialists (“hedge funds” weren’t yet a thing as it were) in 1989, and they were because their cost could be measured in the thousands despite how expensive they were to use (remember roaming charges?), how poor the reception was, and how awful the battery life was. Nowadays a mobile phone brings new meaning to common.

Which brings up its own story. About it, technologist Bret Swanson was the source of the Tandy anecdote that begins this piece. Swanson likes to compare prices of technology throughout time, and some of his most exciting work has come in recent years with the growth of the iPhone. Figure that the brick size mobile phones of the late ‘80s were just that: phones. iPhones are actually supercomputers that fit in our pockets. Not only can we make calls on them that cost next to nothing, not only can they guide us anywhere we want in the world without having to annoyingly stop to get on a payphone in search of directions (the latter was the norm in 1989, and for more than a few it was still the norm in 2009), but they can also enable free global calling via Facetime. Though a simple voice call from Dallas to Ft. Worth once again used to be very pricey, nowadays individuals can talk to their loved ones from anywhere in the world, while seeing them, and there’s no bill to contest for doing just that. Back to Swanson, by his calculations the technology that makes these smartphones extraordinarily super would have set consumers back many, many millions not too long ago, assuming it had been around. The iPhones of today retail for roughly $500-$1,000, but can be had for quite a bit less assuming the buyer enters into a contract with a wireless provider.

Of course, the supercomputers that we carry around, and that are ubiquitous wherever there are people (rich and poor) in the U.S. (and seemingly everywhere else), have us connected to the world’s plenty. Though an interest in a specific book, restaurant, airplane route or clothing item would have potentially required endless amounts of research, expensive calls, interminable delivery waits, and frequently a lot of driving amid an often fruitless search in 1989, nowadays we can tap those computers made for us by billionaires only to summon books, restaurant information, airplane tickets and anything else that interests us from around the world. What about rides? Oh yes, that’s taken care of. In 1989 people were still familiar with taxi dispatchers who seemingly resembled Danny DeVito (most famous then for Taxi – look it up) in both voice and level of rudeness. Now we just tap an app icon on those trusty computers sitting in our pocket only for a driver to appear who knows our name, our route, and whose ongoing employment depends on our being endlessly satisfied.

It would be easy to go on and on, but hopefully the overly uneasy Eric Levitz and all those who think as he does rethink their unease related to the wealth of the “1 percent” having grown by $21 trillion. They should lament that it wasn’t $42 trillion, or $100 trillion. Indeed, imagine how much easier life would be for rich and poor alike. Wealth is created, not divided up. Steve Jobs didn’t hurt Levitz, nor you the reader. He just created.

As opposed to soaring inequality hurting the poor as Levitz so naively presumes, it’s in fact the greatest enemy that poverty has ever known. The wealth gap that has the triggered Levitz in the fetal position is just a happy sign that the lifestyle gap between the rich and poor is shrinking. Levitz can relax. The rich have gotten that way thanks to a world that shrinks figuratively by the day such that the super-talented can increasingly change the world with their tech discoveries. His life would be endlessly frustrating without the superrich, and so would all of our lives be.