The Anti-Federalists Turned Out To be Right – But No-One Reads Them Any More.

What does the Constitution protect? “If you talk to somebody on the street,” he might say “it protects my right to speech, or it protects my right to go to church, or it protects my right to petition my government,” Judge Andrew Oldham says. “Or in Texas, it protects my right to keep and bear arms.” In other words, when you mention the Constitution, most people think of the Bill of Rights.

If you ask who created the Constitution, most people would list well-known Founders like James Madison, Alexander Hamilton and John Adams. During the debate over drafting and ratification, these men were known as Federalists. They designed the constitutional structure, yet they resisted including a Bill of Rights.

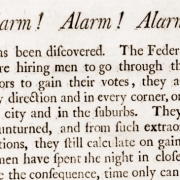

In 1789, when Rep. Madison introduced the first 10 amendments in the First Congress, he was making a concession to the Anti-Federalists. Those writers and politicians—including Robert Yates, Mercy Otis Warren and Richard Henry Lee—opposed the original Constitution. Partly because they lost, their arguments are poorly understood today. Their papers are out of print, most law students never read them, and no one sings about them on Broadway.

Judge Oldham, 40, seeks to raise their profile. A former clerk for Justice Samuel Alito and general counsel for the governor of Texas, he became one of the youngest judges on the federal bench when the Senate confirmed him to the Fifth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in July 2018. He quickly earned a reputation as one of the judiciary’s most intellectually ambitious members, and he’s making a public case that the Anti-Federalists can enrich the legal community’s understanding of the Constitution’s original meaning. They matter, he tells me, not merely because they secured the Bill of Rights but “because of all of the things they said” during the ratification debates.

“We understand what the document itself meant in 1787,” Judge Oldham says, through the “dialectic” between the Federalists and the Anti-Federalists. Many arguments in the Federalist Papers—in which Hamilton, Madison and John Jay made their case for the Constitution—were rebuttals to Anti-Federalists who published first after the Constitutional Convention. “They’re talking to each other,” Judge Oldham says. Reading them against each other “shows you what people thought the document was doing.” Yet few of today’s jurists—Justice Clarence Thomas is a notable exception—frequently cite the Anti-Federalist Papers.

The Anti-Federalists’ arguments were often “scattershot,” Judge Oldham says, partly because they “weren’t collaborating in the same way” as their Federalist rivals. But they all worried that basic liberties were at risk “if we have a new federal government that has new power, and no Bill of Rights.” The Anti-Federalists would ask: “What if Congress does X, and it’s going to abridge my rights?” The Federalists would reply: “Congress can’t do X because Article I, Section 8”—Congress’s enumerated powers—“doesn’t have that power in it.”

Yet the Anti-Federalists’ reading of history was that “our rights are secure when we write them down on paper,” Judge Oldham says. Their models were the 1628 Petition of Right and the 1689 English Bill of Rights. States ended up ratifying the Federalists’ Constitution “on the premise that it would have these amendments to it.”

Judge Oldham is impressed by the prescience of Anti-Federalist concerns “about the way executive power would evolve over time.” In a forthcoming paper for the New York University Journal of Law & Liberty, he quotes the Anti-Federalist Cato (thought to be future Vice President George Clinton), who wrote that the presidency would “create a numerous train of dependents” in the executive branch, so that the president would end up “surrounded by expectants and courtiers”—an aristocracy, which might be compared to today’s Washington elite.

No one in the 18th century could predict the form the federal bureaucracy would take in the 20th century. Yet the Anti-Federalists’ concerns are telling. They worried about “the capaciousness of executive power,” Judge Oldham says, comparing it to “the abuses of the past that they’d seen in England.” The Federalists countered that the separation of powers would prevent any part of the new federal government from becoming too powerful. The legislative, executive and judicial branches were coequal and would check and balance one another.

Yet in recent decades, as Christopher DeMuth has written, “Congress has delegated its lawmaking powers: voting by lopsided margins for goals such as clean air and equality of the sexes, while leaving the hard choices—the real legislating—to specialized executive-branch agencies.” These administrative agencies not only make rules but enforce and adjudicate them—carrying out the functions of all three governmental branches with nary a check.

Polarization has accelerated the growth of the administrative state. With the elected branches divided, more power has fallen to the bureaucracy. The Anti-Federalists, in their way, foresaw this. They worried that a large country would be too divided to govern effectively. They wanted a “small republic”—even 13 states “was enormous to them,” Judge Oldham says. “If the people in Georgia and the people in New Hampshire have very different conceptions of . . . what government is, what liberty looks like, or what people are supposed to be doing with respect to their government,” the Anti-Federalists thought, then “their public officials are going to be pulled in different directions,” and “everybody is going to be disaffected and frustrated.”

Madison and the Federalists, by contrast, argued that “the bigger the country gets, the more Georgias and New Hampshires we have,” the better—that polarization can “create a stasis that preserves liberty,” Judge Oldham says. Madison, he adds, would have been shocked if you told him the Constitution would endure for 40 years, much less 240. Yet as the Anti-Federalists predicted, polarization has put American governance under strain.

The Federalists and Anti-Federalists, Judge Oldham says, were “worrying about the same sorts of stuff that we worry about today”—to wit: “Is my government being responsive to the people? Do we want it more responsive, or less responsive? If we want it more responsive, are there going to be consequences to having it more responsive?”

The Anti-Federalists were concerned government wouldn’t be responsive enough. “There’s a strand that runs through Anti-Federalist thought that is kind of anti-elite, or populist,” Judge Oldham says. They envisioned a constituent talking to his members of Congress and expecting them to “do what I ask them to do—basically speaking for me.” The Federalists, by contrast, feared that a hyperresponsive federal government would descend into mob rule. They were more comfortable delegating power to elected officials to “use their best judgment.”

Which brings us back to the administrative state. In Mr. DeMuth’s view, the rise of populism in the U.S.—and elsewhere in the West—is in part a reaction to the rise of “declarative” government by unelected bureaucrats and judges. Court cases about administrative law don’t make as many headlines as those about hot-button issues like abortion or racial preferences, but they get to the core Founding-era question of who makes the law. “The legal argument is, who decides?” Judge Oldham says. “There’s an agency; there’s Congress; there’s the courts. And the whole discussion is about, where do you put the locus of the decision-making?”

Many conservatives hope that the federal courts could play a role in moving decision-making back to Congress, reinvigorating representative government. Defenders of the administrative state counter that experts need wide deference to manage a complex society and economy. Are its opponents like the Anti-Federalists—clinging to an outmoded form of government in the face of massive change that makes new institutions inevitable?

While they abhorred unaccountable executive power, taking the Anti-Federalists seriously could also argue against muscular judicial interference in the administrative state. The Anti-Federalists worried about an all-powerful federal judiciary impinging on the elected branches and the states. In Langley v. Prince, a decision last month upholding a murder conviction, Judge Oldham himself cited the Anti-Federalists to argue for judicial restraint: “The principal Founding-era concern regarding the scope of Article III was that it could empower federal judges to run roughshod over state courts,” he wrote. “Few things bring this concern into sharper relief than using logic games in federal habeas to set free from state custody a thrice-convicted child-murderer.” He included a citation to an October 1787 essay by Brutus (thought to be Robert Yates), prompting a colleague to quip in dissent: “I had thought the Anti-Federalists lost.”

Judge Oldham declines to comment on his Langley opinion, and he plays his cards close to his chest when it comes to how much the judiciary should get involved in reviewing the decisions of federal administrative agencies. But he notes that the horizons of administrative law have changed dramatically over his young career. When he was a law clerk, it was “an article of faith” that administrative agencies would enjoy vast deference in legal challenges: “We have Chevron , we have Skidmore, we have Auer, we have Seminole Rock”—all Supreme Court decisions requiring judges to defer to executive-branch agencies. The “intellectual puzzle” was “how do we apply them, or which one applies.”

Today, “the way the scholars are writing about it, the cases the courts are granting—they’re reconsidering everything.” One of the scholars he has in mind is Columbia Law School’s Philip Hamburger, who likens the power of administrative agencies to the “royal prerogatives” of 17th-century English monarchs, which provoked the American Revolution.

In the term just concluded the Supreme Court decided two important cases on administrative law. In one, Gundy v. U.S., the justices upheld the delegation of lawmaking power to the administrative state 5-3—but Justice Brett Kavanaugh didn’t participate, and Justice Alito asserted in a concurring opinion that he was open to overturning the precedent in a future case. In the other, Kisor v. Wilkie, a majority composed of the four liberal justices and Chief Justice John Roberts said courts still must defer to administrative agency’s interpretations of their own rules—the Auer precedent Judge Oldham mentioned—but issued new guidance for lower courts that limits agency power.

Judge Oldham suggests the decisions raise more questions than they answer. If these are “either exciting or perilous times for administrative law,” Gundy and Kisor make them “even more exciting, or more perilous.”

Liberals and conservatives are deeply polarized on the administrative state. So were the Federalists and Anti-Federalists in the late 18th century, yet they had a common tradition. Judge Oldham notes that “they’re all naming themselves after leaders of the Roman Republic”—Publius, Brutus, Cincinnatus—because they all supported republicanism and believed “the only legitimacy of the government” was that it acted on behalf of the people.

For all their disagreements, today’s left and right also believe this. But intense polarization, as the Anti-Federalists recognized, can create a fertile ground for tyranny. That makes fidelity to the Constitution all the more important, and reading the Anti-Federalists and the Federalists together can aid that project. Judge Oldham cites Sir Thomas More in Robert Bolt’s 1960 play, “A Man for All Seasons,” on the importance of always being faithful to the law, even when it doesn’t suit one’s immediate purposes: “If we cut down every law in England to get after the devil, then when the wind blows, and the devil turns round on you, where do you have to hide, with all of the laws of England being laid flat?”

In building the administrative state, progressives have aimed at vanquishing many devils—and in some cases succeeded. Yet they might have stretched the limits of the nation’s fundamental law in the process. The election of Donald Trump ought to bring home the risk that the devil may one day turn round on them.

This article appeared at wsj.com on July 6, 2019. Mr. Willick is an assistant editorial features editor at the Wall Street Journal.